Our staff share their favourite

1. Rabbit Syndrome: Australia and America

Don Watson is one of the best writers in Australia: sentence for sentence, his words move along better than just about anybody else’s. His prose is dry and clean, but fattened here and there by vernacular and a good plump sense of the ridiculous. Anyone who is interested in Watson’s writing should read, or reread, his only

Quarterly Essay

,

Rabbit Syndrome

, because in it, he goes deeper and darker, I think, than in any of his other books or essays. Paul Keating once called Watson a ‘fruit bat: he loves to feed in the dark’. That, you might think, is just a cry from one fruit bat to another, but in

Rabbit Syndrome

, Watson lets himself say some specially dark, and really heretical, things about Australia.

At the heart of the essay is the idea that we – Australians – have always been the kept rabbits of the English, or the Americans. And because of this ‘fairly loathsome’ military, political and cultural dependence, we’ve not started up much in this country. After 200 years, there’s just not much here. Great beaches. Good food. Sport. But no nation; we’re more a very large resort, with some mines and industrial farms to pay the bills. We destroyed the aboriginal culture, but never made one of our own. Watson ends Rabbit Syndrome with the suggestion that if we’re not going to do more with the place, taking all our culture from America, we may as well just give Australia to them, and become the fifty-second state. As Watson says: ‘it’s better than ANZUS.’ And at long last, ‘we wont have to go on pretending our soul’s our own.’

All of that is a lot from a man who used to write speeches for Australia’s national leader. Of course, Watson wrote speeches for Keating, and Keating at least tried to make us more independent; Rabbit Syndrome is partly made from anger at how we quickly we re-rabbited under Howard. But it’s also possible to read the essay as a mea culpa for thinking, along with Keating, that Australia could keep its capitalism under control. Keating always made capitalism seem exciting, or like a kind of bravery: ‘opening up Australia to the world.’ Here, in 2003, Watson has more of a sense that we mostly ‘opened’ ourselves for a lot of crap stuff ‘straight from the American blender’. And, perhaps, more of a sense that nothing from the Labor party has ever been strong enough to turn that blender off.

But no matter how far he now is, or isn’t, from the Labor party, much of Watson’s best work has come as a reaction to what he had to do in government. When he was in, we got something as good as the Redfern Speech. Once he was out, we got Death Sentence, and this fine, radically sceptical Quarterly Essay.

2. Unfinished Business: Sex, Freedom and Misogyny

Every woman should read Anna Goldsworthy’s poignant

Quarterly Essay

–

Unfinished Business: Sex, Freedom and Misogyny

. Goldsworthy skilfully dissects life for women in the twenty-first century and why many reject the feminist tag in the age of social media, popular culture, in the workplace and society at large. With influences from Facebook to

Fifty Shades of Grey

,

Girls

to Gonzo porn, what are young women being taught about a woman’s place in the world?

It’s a shame that such issues as equality for women even need to still be discussed in the fiftieth edition of the QE, but looking at the statistics, it’s obvious there is still a real need for discussion on this topic. For example, while some argue that women in Australia have it all – then why do women still earn on average 17% less than men for the same job in our own country? And why – in an Essential Research study commissioned by Crikey – did 61% of women perceive more criticism in the treatment of Julia Gillard as Prime Minister than a male politician would receive, compared to 42% of men?

That 19% represents the difference between male and female perception on this issue and this QE begins to explore some reasons why. One of Goldsworthy’s key areas in the essay is why there are so few women in politics – and why did Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech resonate with women worldwide?

Interestingly, many people who are reluctant to identify as feminist embrace the word ‘misogyny’ – and even more interestingly the Macquarie Dictionary recently expanded the definition of misogyny from ‘hatred of women’ to incorporate ‘entrenched prejudice against women’. There is a big difference between the two. In her essay, Goldsworthy correctly writes: ‘Feminism must be larger than spot the misogyny, but does this mean misogyny should go unremarked?’

Influential Austrian-born Australian feminist, Eva Cox, said that second-wave feminism ‘changed the structures but … didn’t actually change the culture’. But how do we change the culture? One of the key messages of Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech is that we are certainly not done with feminism yet. Everyone has a lot to learn from feminism, even beyond equal pay, the vote, bodily autonomy, the right to own property and the right to have an education.

This is our shared project – our unfinished business.

3. Political Animal: The Making of Tony Abbott

Nobody writes a

Quarterly Essay

quite like David Marr – they are always game-changers, illuminating things not just about one person but about our entire nation.

If you haven’t read Marr’s brilliant essay on Tony Abbott, now is the time to do it. It reveals fascinating truths and contradictions about the man who is leading our country. As he did with his essay on Kevin Rudd (and his new essay on George Pell) Marr digs to the heart of who Abbott is, why he wants power and how he has gone about getting it.

This is the essay where Marr uncovers the now infamous punching-of-the-wall incident (where Abbott allegedly punched the wall beside a young women’s head when she beat him in a university election). Reading various accounts of the story and seeing a young Abbott through other’s eyes is fascinating.

Marr also explores other controversial moments from Abbott’s past, including his relationship with nineteen-year-old Kathy McDonald that ended with her pregnancy, Abbott’s attempts to join the Catholic priesthood and his often unflattering thoughts on women and gay marriage.

Marr recently won the John Button Prize for this controversial essay, and he deserved to. Now that Abbott is Prime Minister, this is perhaps the most important Quarterly Essay ever published.

4. Us and Them: On the Importance of Animals

Earlier this year I tore through Anna Krien’s

and loved it so much, I decided to read her other books, including her

Quarterly Essay

. Spoiler alert: it’s fantastic.

The essay is riveting and important, popping up in multiple award lists. (The title was shortlisted for both a Walkley Award and the John Button Prize, and also won the inaugural 2012 Voiceless Media Prize for print.) Anna challenges us to confront our own complicity in the treatment of animals. She’s not interested in asking whether this treatment is just or not and writes: ‘That age-old debate is a farce – deep down we all know it. The real question is, just how much of this injustice are we prepared to live with? That is the premise of this essay.’ To tackle this premise, Krien divides the role of the animal into three: she investigates the live cattle trade in Indonesia (the animal as food); she takes a close look at testing and experimentation (the animal as scientific material); and looks at the issues related to hunting in Australia (the animal as vermin). Each new interpretation is revealed to us though her measured, journalistic perspective that allows both sides to be heard. It was a perspective I found challenging given I’m so heavily weighted to one side already.

I’ve always been aware of my interactions with animals – I’ve been a vegetarian for about eight years and have grown up with various pets – and I’ve read books about this topic before, such as Jonathan Safran Foer’s Eating Animals. All this means that I thought I was pretty knowledgeable on the subject, but Krien’s essay forced me to reconsider my motives once again. I felt upset, guilty, unsure of what my actions should be – especially where our family pet dogs were concerned. Because she comes at the subject from an Australian perspective, the content felt more personal and more relevant than most other literature I’d read on the topic.

So, even though this QE didn’t provide answers to all my big questions, what I learnt prompted an inner dialogue, one I think we should be making public. And that’s why I think you should read this book.

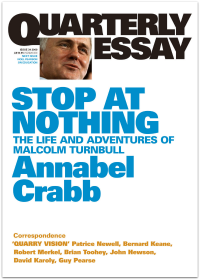

5. Stop at Nothing: The Life and Adventures of Malcolm Turnbull

Biographies of opposition leaders who were only ever opposition leaders have their own fascination, that of an alternate universe that stays so very, very alternate: ‘The Prime Minister, Mr Sneddon, announced today …’ ‘The Prime Minister, Mr Peacock, denied that …’ ‘The Prime Minister, Mr Hewson …’ ‘Mr Downer …’ ‘

Dr Nelson

.’

But that’s enough.

If you think that Malcolm Turnbull is any more likely than those other non-Prime Ministers, you should read Annabel Crabb’s Quarterly Essay – Stop at Nothing. I know there’s a surprisingly large amount of people who still turn their Despair at Abbott into Hope for Turnbull, as if Abbott’s bad, by some natural law, has to make Malcolm good. But if the name ‘Godwin Gretch’ doesn’t bring back some necessary memories, this essay contains proof enough that Malcolm has his own bad, and of the kind that means he could never become that rarest of things: a successful political leader.

For Crabb makes it plain that for all Turnbull’s extraordinary skills, as lawyer, as businessman, as fixer, he has no patience, no feel, for the long, dull work of political persuasion. Even as moody and driven a politician as Paul Keating knew that politics always comes with party, and party means party room votes, and party room votes mean having to humbly explain yourself to ‘colleagues’ who are too stupid, or selfish, to give you a fair hearing. ‘Watering the plants,’ Keating called it. And he did it for years. Turnbull was like Rudd: always doing things the colleagues found out first from television.

This essay also contains a very interesting sub-section on the additional, social-structural reasons why Turnbull, the cultured financier, is now especially unsuited to lead the Liberal Party. Crabb cites academic research comparing the Liberal party rooms of 1975 and 1996. ‘75 is a room full of Old Boys from Australia’s richest schools. But the class of '96 are almost all outer-suburban people: a big bunch of Jackie Kelly’s. The party of the Anglican Ascendancy has become, under that toiling Methodist John Howard, a party made from the lower-middle and 'aspirational’, i.e.: cashed up, working classes. Crabb tells the story of George Brandis, Old Oxonian, asking the rest of the party room if it is really Liberal policy that a hairdressing certificate is as good as a PhD. Howard laughs at him, and says, ‘Oh George. At least you have more chance of making some money with a hairdressing certificate.’

And so, on to Tony Abbott, who understands, as Malcolm Turnbull never did, what the Liberal party has become, and how government in Australia can be won and made almost entirely from what Mungo MacCallum calls ‘Slogans for Bogans’. Under Howard, and now Abbott, we are, more and more, a country of rich bogans. And we’ve got a fair few more years of that to go. As the earth slowly gets hotter.

We need someone. But don’t waste time wishing for Turnbull: he was never the one.

Browse our full collection of