Nicki Greenberg looks back at adaptations of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s classic, from Francis Ford Coppola’s 1974 screenplay to

I first read The Great Gatsby when I was 17 years old. I was captivated by it: by the beauty, the melancholy, the grand yearnings and grown-up extravagance that hummed on a frequency outside the range of my experience. I had to stretch to touch that floating, tarnished world, and just as my fingertips grazed its edges, it would elude me again. I have since read the book many times, and I marvel at the way it yields something different with each reading. Gatsby at 17 is a different experience to Gatsby at 25, at 30, at 37. It is part of the book’s magic that it continues to offer new facets as the reader’s position shifts, and yet its mystery, its feeling of slipping through our fingers, remains.

This glimmering mystery poses a special challenge when adapting the text, whether for the page, stage, screen or any other medium. If we try to pin the book down too forcefully, to fix it with one particular vision, we run the risk of diminishing it. The task, I feel, is not to attempt to pluck out the mystery of the book, but to cradle it, to turn it gently in our hands and allow different lights to play on it so that a reader might see new gleams of meaning flash across it.

For a number of people I have spoken with over the years, Francis Ford Coppola and Jack Clayton’s 1974 film adaptation of The Great Gatsby, with Robert Redford in the title role, is their principal, or only, vision of what the novel is all about. This saddens me, because the film not only failed to do justice to the novel but, in my view, did it an enormous disservice. A quick skim of reviews written at the time suggests that critics largely agreed. This month, there will be another film version of Gatsby, and perhaps this new extravaganza – in 3D, no less – will become another generation’s vision of the book, for better or for worse.

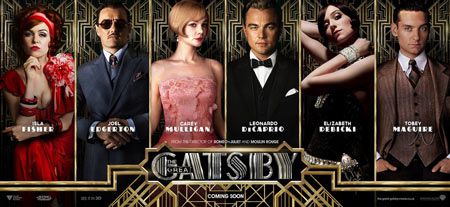

Movie poster for Baz Luhrmann’s upcoming film adaptation.

I watched the Coppola/Clayton version some 20 years ago when studying the novel for my Year 12 literature class, but had never revisited it until very recently. This was mainly because I didn’t enjoy it the first time around, and then because I didn’t want it to skew or get in the way of my own adaptation of the novel. Film images are incredibly potent, and they seem to burn a more powerful impression into our minds than the more subtle ones conjured up by reading a piece of prose. This can happen whether we like the film or not. I feel fortunate that Fitzgerald’s novel was so moving and important to me that it completely eclipsed any memory that I had of the film. Watching it 20 years later, it affronted me all over again.

Gatsby does pose some especially tough challenges to translation for the screen, partly because of the contemplative, introspective nature of Nick Carraway’s narrative. The 1974 film couldn’t seem to make up its mind about this, muddying his voice and his particular point of view. It lurched through the plot and charlestoned through the lavish party scenes, relying heavily on an overblown recreation of the novel’s exterior surfaces – the costumes, the cars and the meticulously constructed sets. As a result, the meaning and the mystery of this most subtle and supple novel, and the luminosity of the prose that made it, is lost.

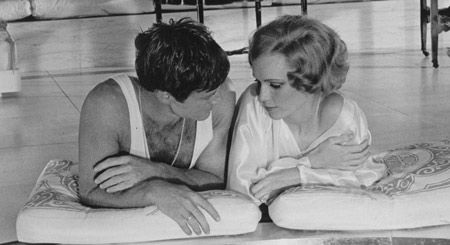

Robert Redford and Mia Farrow (1974)

Coppola also rewrote the story primarily as a grand romance between Gatsby and Daisy. This is simply not what the novel is about, and the attempt to make it so – presumably because Hollywood loves a love story – makes a nonsense of it. Fortunately for Nick, he was not present during the interminable soft-focus scenes of their affair to report clangers like these:

‘Kiss me! Be my lover! Stay my lover!’

‘It was fine for you – breaking my heart with your impossible love!’

‘Put on your uniform and let’s turn off all the lights except for a single candle, and I’ll let you tell me you love me.’

This was not the only startling departure from the book. Over and over again, Coppola rejected the novel’s scenes of perfect delicacy, wit and irony – scenes that are a gift to a screenplay – and replaced them with his own heavy-handed inventions. Adaptation is certainly a creative process, but an adaptor’s impulses must be guided by the meaning, tone and form of the original text. This demands subtlety, restraint and, most importantly, constant, sensitive listening to the book. Coppola’s failure to really listen, while focusing obsessively on the visual, is where I think the film came unstuck.

By contrast, in 2009 I saw the most astonishing and brilliant adaptation of Gatsby – a production called Gatz, by New York theatre company Elevator Repair Service. The show incorporated a verbatim recital – almost completely without notes – of the entire novel. It lasted seven hours and was utterly captivating. In a dilapidated office, a bored clerk finds a copy of The Great Gatsby in his desk and begins to read aloud. As he is drawn into the novel, the clerk imperceptibly shifts to become the voice of Nick Carraway, while his co-workers and various passers-through assume the roles of the other characters.

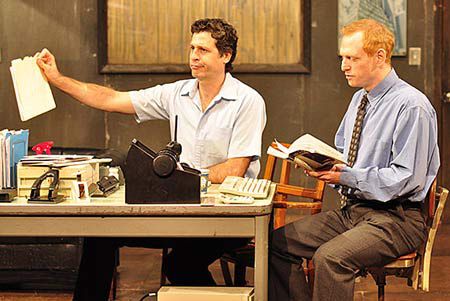

Gary Wilmes and Scott Shepherd in Gatz.

This was adaptation at its finest: faithful to the novel and also thrillingly original. The play illuminated every word of the novel’s wonderful prose, while riffing on the wry humour of the text with an incongruous setting and surprising cast of characters. Nick’s role as a semi-reluctant witness, both ‘within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life’ was perfectly reflected by the clerk-narrator, drawn into the story by a force outside his control – the force of the story itself. Without a single sequin, without lavish sets or cars or costumes, Gatz evoked not only the Jazz Age ambiance of the novel but, more importantly, its complex and mysterious heart.

Gatz is a beautiful example of a group of artists pursuing a dream that for many years must have seemed crazy. A seven-hour play? Imagine the emotional and physical demands on an actor who must memorise, and then recite, the entire novel. Imagine the leap of faith and the huge amount of work by all involved in bringing this play into the world. Positively Gatsbyesque!

Perhaps in order to make an adaptation of Gatsby that resonates, one needs something that is impossible to manufacture. Not a gigantic budget or eye-popping special effects or a scriptwriting holiday on location in Long Island, but a very large dose of passion, ‘a romantic readiness’ and sensitivity as open and extravagant as Gatsby’s own.

Nicki Greenberg’s graphic adaptations of