Discover the new nonfiction books our booksellers are engaged with this month!

The Last Outlaws

Katherine Biber

On a midsummer’s morning in 1901, a Wiradjuri and Wonnarua man was hanged for murder at Darlinghurst Gaol. What marked the end of Jimmy Governor’s life was the newly Federated nation’s first blood: an act which deepened routinised violence against Indigenous peoples and set the wheels of systemic racism in Federal law into its most extensive motion.

Katherine Biber’s The Last Outlaws, developed from her NSW Premier’s History Award-winning podcast of the same name, meticulously tracks Jimmy’s story through written and oral records to illuminate a far broader history of colonialism’s legal machinery. Jimmy and his brother Joe were the final two men in Australia proclaimed outlaws after the murders of Sarah Mawbey, three of her children and their schoolteacher Helena Kerz. Rather than examining Jimmy and Joe’s actions as isolated incidents, Biber maps how persistent humiliation, dispossession and brutality through the brothers’ and their family’s lives fostered circumstances capable of begetting further violence.

Biber’s ability to slip seamlessly from past to present, from open wound to aching scar, gives The Last Outlaws a rare immediacy few writers of legal history can sustain through a saga as far-reaching as the Governors’. In clearly articulating how the threads of Jimmy and Joe’s cases form the tapestries of our current judicial, political and cultural frameworks, Biber’s resolute and compassionate account provides much-needed context for understanding the full scope of the last two centuries of Australian history. With an eye to the future of reconciliation, The Last Outlaws unravels the legacies of injustice that continue to haunt courtrooms and Country, challenging us to look beyond the punitive and toward truth-telling.

Reviewed by Gene Pinter.

Deep History: Country and Sovereignty

Edited by Ann McGrath & Jackie Huggins

At numerous points across the 12 fascinating essays that make up Deep History, the collection’s many contributors offer definitions of ‘deep time’ and ‘deep history’ that foreground the concepts’ importance to building a just and informed national identity. The idea at play is both richly nuanced and effortlessly simple: the history of Australia did not start in 1788. Indeed, ‘deep history’ extends far, far beyond the inception of colonial Australia, and into the tens of thousands of years of Indigenous occupation and ownership of Country that preceded it. It is a history made no less legitimate by the absence of written records – the benchmark of Western historical practice – and instead one that invites new forms of evidence: oral traditions, material culture and the land itself. By acknowledging this history, the collection argues, we might deepen our understanding of Australia’s past not only quantitatively but also qualitatively, upending the conceptions of time and history that subconsciously shape our thinking.

Deep History is a work of high-level academic reflection and vibrant digression, and I thoroughly enjoyed reading it. As an anthology, each essay wields a degree of independence with which the authors explore topics ranging from literary analysis of Tara June Winch’s fiction to an archaeological account of the preserved tracks at Lake Mungo. Such breadth of focus also manifests geographically, with chapters on traditional Māori food cultivation or the power of oral memory in Papua New Guinea, presenting both variation and congruence with our familiar Australian contexts. Nevertheless, within this variety, each essay maintains a steadfast commitment to the defining principle of Deep History: that to draw some line between colonial history and Indigenous prehistory is to erase the continuity and persistence of First Nations’ cultures and consign them to the past. Such erasure silences voices. Deep History, as this collection argues, empowers them.

Reviewed by Joe Murray.

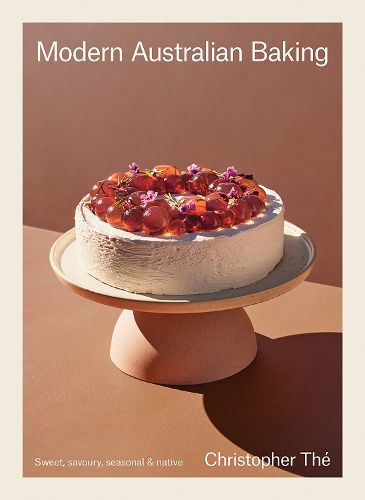

Modern Australian Baking: Sweet, Savoury, Seasonal and Native

Christopher Thé

Before you take home this most beautiful ode to baking by Christopher Thé, founder of Black Star Pastry and creator of ‘the world’s most Instagrammed cake’, I’m going to help you with some tips:

- You can purchase saltbush already ground, ready to use from your local deli or very good IGA.

- All Australian nuts are actually very easy to source. I purchase mine from my local market.

- Warrigal greens are relatively easy to get from any veggie shop.

- Yes, you should buy at least one fresh Australian truffle in your lifetime. (For one the size of a golf ball, it’ll cost you around $50 but can be used in several dishes. It is bang for your buck!)

- Reading this book may influence you to start collecting pastel-coloured dinnerware. This is not necessary. The food will taste just as good without it as long as you follow the instructions: for the love of everything sweet, do not rush the steps. There is no point; you will only be disappointed.

Sydneysider Thé is internet famous and for a good reason. His food is utterly picture perfect and delicious. This book is a new type of baking bible which includes all the classics: bread, dough, pastry, cakes, biscuits and adds a sprinkle of Australian influences. For example, his saltbush scones are a revolution in your mouth with a deep, salty, earthy and sweet taste all at once. The winter chapter holds one of the most delicious recipes I’ve come across: truffle custard tarts. (Even writing it here has made my mouth water). And the best news is that it is as easy as pie to make.

This is the baking book you’ll keep reaching for. It’s possible you’ll buy it for a visiting friend but, truly, a better arrangement for everyone involved would be a jar of desert-lime marmalade (recipe included in the Summer chapter) for them, following the purchase of a new and pretty baking book for you. Modern Australian Baking: not just for those who photograph their food.

Reviewed by Chris Gordon.

Sweet Nothings: Power, Lust and Learning

Madison Griffiths

Author, artist, and producer Madison Griffiths rips off the band-aid 30 years after Helen Garner’s controversial book The First Stone and launches a new discussion about abuse, sex and power dynamics in Australian academia. Told through the accounts of real women, research, and personal experience, Griffiths is an unflinching voice in Australian feminist literature today.

Sweet Nothings delves into the stories of four women – Rose, Blaine, Cara, and Elsie – and their experiences as students who embarked on romantic relationships with university professors. Through their accounts, we examine how gender, power and sex is exploited in the university setting, with Griffiths providing a deeper analysis of the cultural and social acceptance and endorsement of imbalanced male-female expectations and authority.

Sweet Nothings almost feels novelistic at times with its tender, poetic prose as Griffiths handles the nuance and complexity of these difficult discourses with care and a quiet fury. Although elements of the story – including the women’s names – have been fictionalised to preserve anonymity, this book is one of thousands of true stories that share the same outcome of exploitation, humiliation and heartbreak following from a ‘sweet nothing’: an empty promise of love and affection that makes you feel special and seen. Griffiths dissects the psychology of the female student and the male teacher – their individual desires, their expectations of what they deserve, and the lasting scars left behind.

Praised by Clementine Ford, Chanel Contos and Hannah Ferguson, Griffiths’ candid and searing style of writing exposes the long history of pedagogy tied to abuse of power, particularly between male teachers and female students. With these stories taking place across Australia, openly naming many highly esteemed universities, Sweet Nothings is a tale that unfortunately feels close to home, perhaps bringing comfort to those who felt they were alone in this experience, but shocking all who learn the true prevalence of these experiences.

Reviewed by Aurelia Orr.

What Artists See: Essays

Quentin Sprague

This delightful collection of essays explores the world through the eyes of an artist. Author Quentin Sprague has been immersed in the art world, variously working as a curator, an art coordinator, a researcher and as an artist. He is well known for his art writing and criticism, as a frequent contributor to various Australian publications, such as the Monthly, as well as writing for exhibition catalogues. His first book, The Stranger Artist, won the 2021 Prime Minister’s Literary Award for Nonfiction.

Sprague’s first essay opens into a scene familiar to many Australians who, like me, have grown up in the country. The long journey home from somewhere bigger and the landmarks that develop through retracing that trip over and over. He talks about the hill his mother named ‘The Birthday Cake’, a name handed down to him and his sister, which became a sign that they had re-entered their home landscape. What might just be a bump in the land for one traveller is a nexus of meaning for another. This beginning builds up the focus on idiosyncrasy across the essay collection, exploring the unique grain of artistic perception that shapes a person’s artistic practice. What does it mean to see the world like an artist?

Sprague is also a talented writer, to say the least. Each of these essays pulls you into a different world. They are grounded in thorough research and interviews with artists. Delightfully, Sprague allows for contradictions and the rough edges to show, the moments of resistance from the artists he interviews, when they refuse the narrative or his framing of them, which creates small but interesting bubbles of tension. I would recommend this book for people interested in the Australian art scene, lovers of biography in general, or even those fascinated by what makes people tick.

Reviewed by Stephanie King.

Bad Friend: A Century of Revolutionary Friendships

Tiffany Watt Smith

This is an interesting title for a historical take on women’s friendships. However, I am not sure it does its subject justice because this book is all about how women support one another, in all the various stages of life. Think of it as a history lesson on how women survive. The title, referenced often, is explained as indicating the way in which some friendships work for a time and then do not. It is about how particular friendships form for one reason or another – motherhood, illness, or even jail – but do not last the distance.

English historian Dr Tiffany Watt Smith has done an excellent job of leading us through the 21st century to illustrate how these friendship cycles have always existed. She moves us through the decades with examples from literature (Enid Blyton even gets a look in), pop culture, films, interviews, workplaces, and historical documents. The references at the end are mind-blowing in their conscientious length and detail.

I liked reading the interviews; the snatches of conversations from various women who have chosen a particular moment in their lives to recount. (After all, the personal is political.) I liked considering my own friendships against the examples she presented. I was drawn to the stories of women in their older years that rallied together to live close to one another in a self-made community: a coven of sensible women. I like that we learn about the author, in a comparable way to that experienced by readers of Lisa Taddeo’s writing.

Bad Friend is full of examples of what women do well – acceptance, encouragement – and what women do fantastically well: disobedience. This thought-provoking exposé on women’s lives is a (needed) reminder of women’s strength and independence. I am buying a copy for my bestie; it is that type of book.

Reviewed by Chris Gordon.

Available from 22 July and to pre-order here.