Rod Moss has been living and painting in Alice Springs for over two decades, forging close ties with the Aboriginal community there. He shares his experiences – and his artwork – in this amazing new memoir

,

.

Barry Hill, award-winning author of

,

spoke to him for Readings’ New Australian Writing feature series

.

Rod Moss, a strongly built, gentle man who arrived in Alice Springs 25 years ago, has a body of work which is unprecedented in the history of Australian painting. This for two reasons: no other talented white Australian artist has mingled for so long with Aboriginal people with as much respect and intimacy. And in these years so much in Alice has got worse: what was once the heyday of land rights, with so much promise in the air, is now poisoned by a death rate among people who might be counted as among the wretched of the earth.

The power of Moss’s realist painting often depends on its revelation of contemporary Aboriginal life in one of the town camps –‘the truth and the terror’ as he puts it: the drinking, the violence, the self-destructive degradations of family life that continues in a blur of sorry business.

At first glance the paintings look exploitative of people’s suffering. But the work– the painting and this writing that recounts the lives that make it possible – has a redemptive quality. Moss’s relationships with people are full of mutuality and trust. The Hard Light of Day is a kind of love story.

The humpy settlement involved in Moss’s life and work is the Whitegate camp, on the eastern edge of town. A supreme irony is that the Hayes family who live there are the traditional owners of Alice Springs: they successfully won their claim of Native Title in 1998, which made little difference to living conditions.

‘Did I come here to go to funerals?’ Moss would ask himself. Within ten years he’d been to 60 funerals: most of them for people under 50, many of him them his friends or their relatives, and whose grief flowed into his own, occupying his dreams.

He stayed on in Alice. His life was there: teaching art at the Centralian College; and his family, the two kids, and their mother. When the marriage broke his family moved south, leaving him as sad as some of his Aboriginal friends. By then, however, his connection with the other culture was a source of fundamental nourishment. His door to them has been open in ways that few other whites can withstand. He’s had a rule that no ‘drunks’ were to come in. But that was no easier to keep than the rule that things were not to be nicked from his house, or that there was a time in the day when he was no longer available to drive his friends to the supermarket, or out bush or even to the hospital.

Meanwhile – and this is a crucial meanwhile – there was joy to be had in their proximity and their trust. The bush outings, the camping and hunting together. His kids with their kids among the bush tucker, at the water holes, as well as around town, or at the Alice Springs show. Normal – interracial – life is as much the subject matter of Moss’s work as the graphic indications of tragedy.

There is humour in the frequently satiric paintings, and there are many funny things in the book: jokes that leap out of the Aboriginal play with English, as well as their lust for life.

Finally, there was Moss’s deepening father–son connection with Arranya, or Edward Johnson, the knowledgeable old man determined to introduce the tender and open-hearted white man into the traditional stories of his country. Over 20 years this took place, and the process informs many of Moss’s paintings which tremble with another thing; that one day, he might, just might, succumb to the standing invitation being intimately pressed upon him by his younger friends: that he too be cut, initiated into manhood. So far he has not. He has stood back inside his own culture. His painting and the lucid, candid writing in this book throbs with ambivalence, however.

I began by asking him to say more about one of the paintings so well reproduced in his book. The Enigma of the Whiteman is a double self-portrait— a white man wrestles with himself in a half circle of Aboriginal men. The white man is naked and the others are not.

RM: You could say that the motive driving the fight within the self is having to resolve the conflict between animistic, pagan beliefs and Christianity. Or the anima/animus. Or the outsider/artist quandary with community. I feel I occupy this liminal between Arrernte ‘believers’ and my own activity as having ‘faith in art’.

BH: And how do they see this struggle, your portrayal of yourself as so naked?

Just a few months ago a friend came to my house… ‘They see you naked,’ he said, of his friends and family. ‘You man. They smile, but they think you man. Naked man. No shame being naked. Proper man. Look, you saying; me man, full man. You got power in your mind.’ He meant, I had power in my mind for painting, just as he has power because he has been initiated into country. ‘You not alone, here’, he said. ‘Just remember.’ This blew me away.

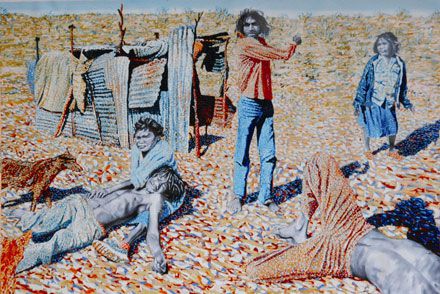

Raft

by Rod Moss, courtesy UQP.

BH: Is their privacy invaded by your pictures?

RM: The painting is a caring thing and the families instantly recognise this. They also like seeing themselves in my pictures … If it’s a tough painting— like Raft, for instance, which shows their drinking, I’ve known them to sit quietly and reflect on their ‘grog sickness’.

BH: The writing in this book. How did it happen, and what are you trying to do?

RM: The book derives from journals I’ve kept for many decades … I wanted to bring a sense of the vividness of encounters I was having on a daily basis and of a kind I had not read anywhere else …

BH: How does the writing connect with the paintings?

RM: Well, it backgrounds, or foregrounds the type of occurrences that erupted into paintings, though I don’t regard the paintings as illustrations of the text. The writing might go some way towards revealing the difficulties in establishing and maintaining relationships. I view them both as a means of reciprocated respect to the people depicted, as kinds of love letters.

BH: Other painters and this kind of writing?

RM: The list of literate painters is long. Van Gogh, Max Beckmann, Donald Friend and so on. I’m not aware of any in regard to cross-cultural data.

BH: There’s Gauguin. But he painted and wrote under the heading of desire. Eros does not arrive in your work. You do nakedness without desire.

RM: That’s right. It hasn’t come into my life with Aboriginal friends.

BH: What have you left out of your book?

RM: Most readers have been shocked by the violence. But I have minimised it, as well as the funerals and the daily grind of running around … I don’t venture into the jealousies of sexual parties, or the politics of family rivalries; the background of these, which really drive daily lives, are not my province to disclose …

BH: How do you stay so calm in the face of such turbulent suffering? The invasions of your life! I think of you as a gifted quietist. Does that fit?

RM: It’s probably traceable to the power structure of my family, adapting to my father’s angry outbursts, my older brother’s merciless bullying – me maintaining my integrity by ‘quietism’: no argument, and certainly no physical resistance on my part. … I’m less interested in having power over people than over the materials of those little rectangles of painted splodges.

BH: What have you learnt from Aboriginal culture?

RM: Affection. Tolerance. Openness. Spontaneity. Physical embracing. Eye for detail. Indifference to acquisitions.

BH: You have gained this even from the people in a deeply damaged community?

RM: The above virtues persist.

BH: Your religious beliefs? How have they informed your life in Alice?

RM: …What are my abiding beliefs? I respond to needs of the needy where and when I can. A lift to the hospital. Phoning a taxi. Collecting firewood. I wouldn’t call it a religious activity. I’m enhanced by responding in this way.

BH: How’s your book been received by the Whitegate mob?

RM: The families are immensely pleased, and it’s a terrific endorsement to see people hug a copy of the book to their chests and exclaim that the book fills their heads with memories, and that they don’t want to let go of the book.

Barry Hill is the author of, among other books,