Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

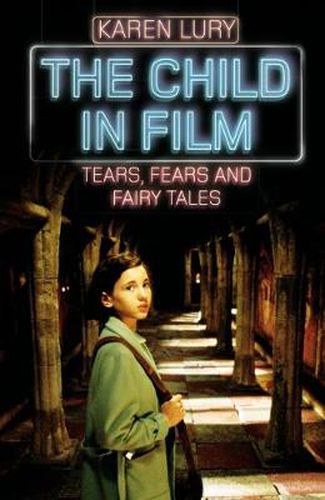

Ghastly and ghostly children, ‘dirty little white girls’, the child as witness and as victim, have always played an important part in the history of cinema, as have child performers themselves. In exploring the disruptive power of the child in films made for an adult audience across popular films, including Taxi Driver and Japanese horror, and ‘art-house’ productions like Mirror and Pan’s Labyrinth , Karen Lury investigates why the figure of the child has such a significant impact on the visual aspects and storytelling potential of cinema.Lury’s main argument is that the child as a liminal yet powerful agent has allowed filmmakers to play adventurously with cinema’s formal conventions - with far-reaching consequences. In particular, she reveals how a child’s relationship to time allows it to disturb and question conventional master-narratives. She explores too the investment in the child actor and expression of child sexuality, as well as how confining and conservative existing assumptions can be in terms of commonly held beliefs as to who children ‘really are’.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

Ghastly and ghostly children, ‘dirty little white girls’, the child as witness and as victim, have always played an important part in the history of cinema, as have child performers themselves. In exploring the disruptive power of the child in films made for an adult audience across popular films, including Taxi Driver and Japanese horror, and ‘art-house’ productions like Mirror and Pan’s Labyrinth , Karen Lury investigates why the figure of the child has such a significant impact on the visual aspects and storytelling potential of cinema.Lury’s main argument is that the child as a liminal yet powerful agent has allowed filmmakers to play adventurously with cinema’s formal conventions - with far-reaching consequences. In particular, she reveals how a child’s relationship to time allows it to disturb and question conventional master-narratives. She explores too the investment in the child actor and expression of child sexuality, as well as how confining and conservative existing assumptions can be in terms of commonly held beliefs as to who children ‘really are’.