Readings Newsletter

Become a Readings Member to make your shopping experience even easier.

Sign in or sign up for free!

You’re not far away from qualifying for FREE standard shipping within Australia

You’ve qualified for FREE standard shipping within Australia

The cart is loading…

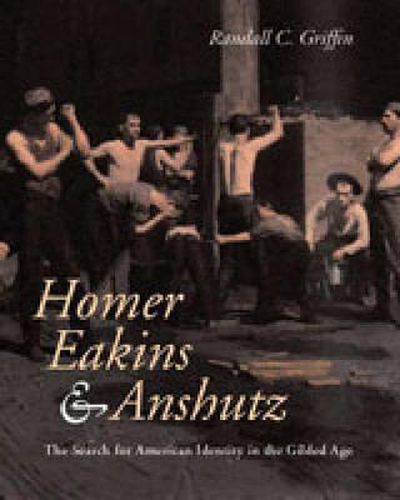

Randall Griffin’s book examines the ways in which artists and critics sought to construct a new identity for America during the era dubbed the Gilded Age because of its leaders’ taste for opulence. Artists such as Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, and Thomas Anshutz explored alternative American themes and styles, but widespread belief in the superiority of European art led them and their audiences to look to the Old World for legitimacy. This rich, never-resolved contradiction between the native and autonomous, on the one hand, and, on the other, the European and borrowed serves as the armature of Griffin’s innovative look at how and why the world of art became a key site in the American struggle for identity.

Not only does Griffin trace the interplay of issues of nationalism, class, and gender in American culture, but he also offers insightful readings of key paintings by Eakins and other canonical artists. Further, Griffin shows that by 1900 the nationalist project in art and criticism had helped open the way for the formulation of American modernism.

Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz will be of importance to all those interested in American culture as well as to specialists in art history and art criticism.

$9.00 standard shipping within Australia

FREE standard shipping within Australia for orders over $100.00

Express & International shipping calculated at checkout

Randall Griffin’s book examines the ways in which artists and critics sought to construct a new identity for America during the era dubbed the Gilded Age because of its leaders’ taste for opulence. Artists such as Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, and Thomas Anshutz explored alternative American themes and styles, but widespread belief in the superiority of European art led them and their audiences to look to the Old World for legitimacy. This rich, never-resolved contradiction between the native and autonomous, on the one hand, and, on the other, the European and borrowed serves as the armature of Griffin’s innovative look at how and why the world of art became a key site in the American struggle for identity.

Not only does Griffin trace the interplay of issues of nationalism, class, and gender in American culture, but he also offers insightful readings of key paintings by Eakins and other canonical artists. Further, Griffin shows that by 1900 the nationalist project in art and criticism had helped open the way for the formulation of American modernism.

Homer, Eakins, and Anshutz will be of importance to all those interested in American culture as well as to specialists in art history and art criticism.