There are many books about gardens and gardening: ‘how to’ manuals on bonsai, lavish photo essays on Italy, scholarly histories of design. Philosophy in the Garden is something else entirely: the intelligent garden-lover’s detective story—less of a ‘whodunit’, and more of a ‘why do it’.

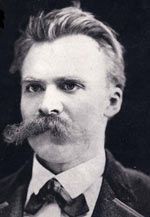

Why was Jane Austen gazing at lilacs instead of writing Mansfield Park? Why was Friedrich Nietzsche wandering in a citrus grove? And why was George Orwell, ill with tuberculosis, hacking at dry dirt with a pickaxe instead of resting?

The answers, it turns out, are deeply philosophical. This is because gardens are a unique combination of nature and humanity. They reveal our relationship to nature: what we make of it, literally and figuratively. They also speak of psyche and society: what it is to be human. Because of this, gardens are more than decorations or badges of status—they can be where our most intimate ideas gain new life.

Jane Austen, for example, was not just avoiding work, or taking a deep breath in her Chawton cottage garden, with its mock oranges and apricots. She was enjoying a kind of cosmic consolation, which she missed when her family moved to Bath, and her writing dried up. The garden reminded Austen of the world’s primordial rhythms: seasons; cycles of birth, growth and reproduction; the comforting cadence of her beloved English landscape. It was an example of Alexander Pope’s lines from ‘An Essay on Man’, which Austen quoted: “Whatever is, is right.”

This vision let Austen know that all was well; that her divine creator’s cosmos was ticking along fine, and she could return to her wonderfully human world of adoration, snark, betrayal and upstanding naval officers.

For Nietzsche, nature was all indifference and profligacy: a lesson in risk-taking and novelty. It took him away from sentimentality and idealism, and pushed him to welcome change: in himself, and the world. But the carefully tended lemon groves also taught style: mastery of his instincts and urges, instead of vulgar egotism or sloppiness.

Importantly, gardens need not be grand or traditional to offer these intellectual gifts. Marcel Proust, for example, at one point kept a bonsai next to his bed: in his mind, it became “a vast forest, stretching down to a river, in which children could lose their way.” This principle works for pelargoniums in a courtyard, succulents on a desk: with a little patience and imagination, what’s small and seemingly banal can be extraordinary.

Ultimately, what unites the authors portrayed in Philosophy in the Garden is not any one ideal, but a devotion to the garden itself: to its philosophical fertility. Despite being bookworms and paper moths, they did some of their best thinking al fresco. (Even Jean-Paul Sartre, whose hero in Nausea was sickened by a chestnut tree.)

And this rare collaborator exists, not in some utopian land, but in our own backyards, in nearby parks, or in a terracotta pot on a porch.

The garden is an intimate invitation to great ideas.

A book by Booki.sh

Damon Young is the author of