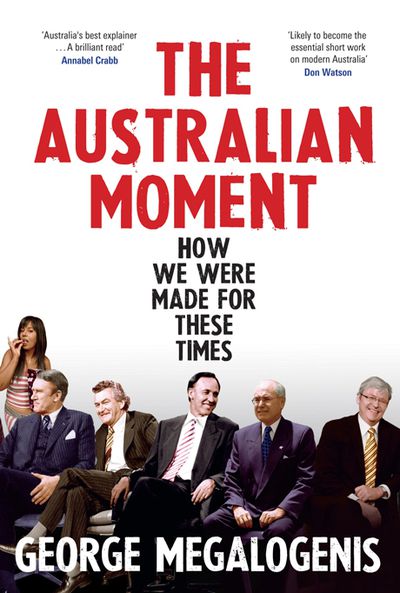

Sean O'Beirne of Readings Carlton chats with much respected journalist and

That’s not a bad start. The idea behind the book was to show how we have changed as a nation and as a people. We’ve moved from being one of globalisation’s whipping posts – most notably, we suffered the worst of stagflation in the 1970s and early 80s – to one of the most resilient, rich nations in the 21st century. The book tries to explain why, and to provoke the debate we have to have: can we take this opportunity to become a great country?

Part of the surprise of the book is how good you think Australia is – how much you think we have achieved. Paul Keating once said he wanted to make Australia more than just ‘a quarry and a farm’. But isn’t that still mostly what we are? A big rich place that’s never had to work very hard to be wealthy?

That was who we were in the 1950s and 60s. But we lost the plot in the 70s, and, it is easily forgotten now, but some very hard work was required to save the place. The economic and social reforms which followed have, I think, set us up for bigger things. The very fact of our great escape from the GFC tells us that we have something the rest of the world would kill for. I’m not just talking about the transactions that got us out of the GFC, but the fact that our society held together. There have been no shopping riots, for instance.

Our economic model, and our immigration program fused by 2008-9 to deliver the most resilient, and less-frightened nation in the rich world. There is more than luck going on here.

What are some of the biggest mistakes we’ve made in the last, say, twenty years? What should we have done better?

The mistakes are easy to pick because they involve decisions avoided. The past ten years have been reform lite in part because our politicians stopped dreaming, and in part because they surrendered to the 24-hour news cycle and the fortnightly polling cycle.

We should have reinvested the first round of the mining boom, not blown it on middle class welfare. We should have done more to secure the water supply. We should have spent more time getting to know the rising powers in our region. We should not have gone to Iraq. And we most definitely should not have scratched the scab of xenophobia with the asylum seeker issue. I could go on.

If we are to do better, what kind of leaders should we have? There seems to be more and more belief among journalists and academics that we should hope for another leader like Keating. Why is Keating so important?

Keating’s prime ministerial voice resonates today in a way it might not have in the immediate aftermath of the ‘recession we had to have’ because it imagines a great Australia. This sort of leadership involves national building from a position of strength, not in response to a crisis. It is, by definition, something we have never had before.

We have enjoyed a period of 20 years of uninterrupted growth and find ourselves with our first ever locational advantage, being the rich nation in the fastest growing region in the world. When Keating said in the early 90s that we have to find our future in Asia, it turned out that he was really speaking to this very moment, when our economy and society was open and the future was Asia’s.

Since the Global Finance Crisis, there’s more opposition not just to this or that problem with markets, but to capitalism itself. Why is capitalism still best? Should we limit the debate about Australia to what leader or party could govern markets better?

Big question. The version of capitalism that led us to the GFC is one that we, in fact, didn’t practise. The question about the future of capitalism is really about the US model.

Here’s the scoop: we have an answer without realising it. Capitalism, left unchecked, and driven by the zeroes of financial transactions (borrowing for the sake of spending) is trip-wired to destroy societies. We know better, and if we can convince ourselves of this, we might a) improve on our model and b) offer the rest of the world an example to follow. If our leaders thought this way they wouldn’t bore us with the old debate of managing prosperity: ‘who do you trust to keep interest rates low’.

What do you see as more likely in the future? In say, the next five years? You’ve argued that Australia is still stuck in the kind of politics made by John Howard, with too much cash given out to working people, and too much protection against outsiders. What could change this?

I am reluctant to predict the future. The Howard model, though populist in nature, proved to be self-defeating. The Abbott version might seem appealing to a confused electorate, but it is doomed by definition because it assumes government is there to placate, not inspire. It may be that we have keep changing governments until we get leaders who are confident in the future. I don’t know how many years our system can indulge the sort of nutty politics we have seen lately before it starts to send the country backwards.

George Megalogenis will discuss