1. Jo March

It’s no coincidence that my name is Jo. Okay, I’m not named after her, but I’ve always identified with Little Women’s tomboyish writer Jo March. The second-oldest of four sisters during the American Civil War, Jo is the driving force of the quartet: she writes plays for them all to act in; she invites the lonely boy in the mansion across the road, Laurie, to be their best friend; and when they’re running low on money, she cuts off and sells her hair (as sister Beth calls it, Jo’s ‘one true beauty!’) to raise funds.

At a time when most women aspired to be ‘good wives’ (the title of the sequel), Jo is determined to make it as a writer. And, perhaps most important for its enduring appeal for young readers, Jo is constantly engaged in a fierce internal battle with herself, striving to be a good person and a good sister and daughter – and fighting the temper that eventually costs her the overseas trip she’s worked towards for years. (In the opening chapter, she reflects that ‘keeping her temper at home was a much harder task than facing a rebel or two down South’.) In her passions, flaws and good heart, Jo is utterly identifiable and lovable.

Even more so because she’s played, in the first and most recent film adaptations, by Katherine Hepburn (1933) and Winona Ryder (1994) respectively: an icon played by my personal icons. The two films are directed by cinematic icons, George Cukor and Gillian Armstrong.

2. Tina Fey

Tina Fey (aka my hero) was famously the first female head writer of Saturday Night Live. More important, to me, are the following three achievements: 1) Creating, writing, producing and starring in 30 Rock, her meta comedy set behind the scenes of a late-night comedy show; 2) Writing Mean Girls, the best teen movie of all time (‘it’s like, the rules of feminism!’), with a part for herself as a divorced teacher with a part-time job at TGI Friday’s; 3) Writing Bossypants, which was such a smash-hit that it’s gone on to inspire pretty much every other famous female comic, from bestie Amy Poehler to the brilliant Mindy Kaling, to write their own memoirs.

In Bossypants, Tina is not just smart, funny and perceptive (of course), but she also unapologetically owns her success as a product of hard work, little sleep and risking failure. She writes about working in the SNL office until 5am (and dealing with male comedy writers who piss in jars rather than walk all the way to the toilet), negotiating script rewrites with Oprah so she’ll appear on 30 Rock, and dealing with annoying questions about gender and comedy, especially the age-old: ‘Can women be funny?’

This book provides the answer: DUH.

3. Nadja Spiegelman

I’m a sucker for a cross-generational mother-daughter memoir. I love the way intersecting individual lives in one family can so deftly illustrate so much: inheritance and environment, the imperfect ways we connect and push each other away, and the way we’re all shaped by the shifting context of the world we live in.

Nadja Spiegelman is the daughter of Francoise Mouly, art director of The New Yorker, and Art Spiegelman, creator of Maus, the internationally bestselling graphic novel about the Holocaust. She’s inherited her inclination to make sense of her world through creative output from both parents. I’m Supposed to Protect You from All This is her remarkable, brilliantly executed memoir. It spans growing up in downtown New York during the 90s (and being evacuated from high school during the 9/11 attacks), her mother’s dysfunctional childhood in Paris with narcissistic, emotionally distant parents, and finally, her Parisian grandmother’s account of her mother’s childhood – and her own.

One of the many things I love about this book is the way it incorporates the process of making narratives and negotiating truth into its very structure, weaving in conflicted versions and allowing the reader to do some of the work of interpreting the ‘real story’ between the lines.

4. Nathaniel Piven

‘Nice guy’ Nathaniel Piven, the protagonist of devastatingly smart and funny novel The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P., is an anti-hero you’ll love to hate. If Jane Austen (or indeed, Edith Wharton) were alive today and wrote about literary New York, this meticulously observed novel would be the result. While its driving conceit – and chief pleasure – is an attempt to answer the question, ‘what do men really think about women?’, this is closely followed by a delicious insider’s satire of what it’s like to be a writer on the lower rungs of the New York literary ladder.

Thirty-something Nate, a transplant to Brooklyn from Maryland, has suddenly found himself sought after by a certain sub-set of women. ‘The well-groomed, stylishly clad, expensively educated women of publishing found him appealing. The more his byline appeared, the more appealing they found him.’ Author Adelle Waldman puts Nate through a series of relationships (or rather, puts the women through them), focusing on one with fellow writer Hannah, whose appeal is in her repartee and intellect as much as her looks.

One of the many reasons it’s hard to put this book down is that pretentious, unaware, recognisably badly behaved Nate is not all bad. In a late-relationship argument with Hannah, responding to her criticism of his entitled arrogance about his writing, despite its shortcomings, he says: ‘His main criticism of her, in terms of writing, was that too often she wasn’t ambitious enough. She should treat each piece as if it mattered, instead of laughing off flaws proactively, defensively, citing a ‘rushed job’. … On top of it, she didn’t seem to be making much progress on her book proposal. Still, he unreservedly thought she was extremely talented. She deserved more recognition than she’d gotten. It wasn’t fair. He told her so now.’

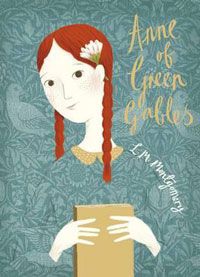

5. Anne Shirley

Red-headed (sorry, auburn-haired) orphan, Anne (with an ‘e’) Shirley in L.M. Montgomery’s 1908 children’s novel, Anne of Green Gables, was one of my earliest literary heroes. Like Jo March, she was a hot-headed young girl with a wild imagination and a passion for storytelling; she was desperate to be good, yet inclined to act on her emotions rather than reason. I think of Anne as the Canadian Jo March.

Of course there are ample differences in setting and circumstance: Anne’s picturesque country idyll of Prince Edward Island, so beloved that it’s now a major Canadian tourist attraction, is a world away from the March sisters’ Massachusetts. And while Jo is at the heart of an enviably close family, Anne was orphaned as a baby, is almost rejected by adoptive ‘parents’ Matthew and Marilla (a brother and sister) because she’s not a boy, and the community of Avonlea, who will come to embrace her, are initially wary. Both are original characters who must work to contain their exuberant difference in order to fit in. Jo acts out knowing she’s loved by her family anyway; Anne must continually earn the love of hers. Anne’s background, barren of love or security before Avonlea, will apparently be brought into focus in the new Netflix series, Anne with an E, by Breaking Bad writer Moira Walley-Beckett.

Jo and Anne both have handsome, clever, funny male best friends who all the girls love, but who have adored only them since childhood. They both reject their repeated marriage proposals. But while Anne eventually relents (albeit several years later) and marries Gilbert Blythe, Jo’s transitory second thoughts, following a family tragedy, dissolve when she discovers that Laurie has married her youngest sister. ‘Girls write to ask who the little women marry, as if that was the only aim and end of a woman’s life,’ fumed Alcott, in between Little Women and Good Wives. ‘I won’t marry Jo to Laurie to please anyone.’ Instead, she compromised by marrying Jo to a German professor who only really becomes romantically appealing in the (1994) film version, when he’s played by Gabriel Byrne.

Finally, both Jo and Anne are passionate aspiring writers who find success with autobiographical novels that are meant to represent the novels we’ve been reading. They contain the implicit hope for young readers that one day, they too, might grow up to write a book.