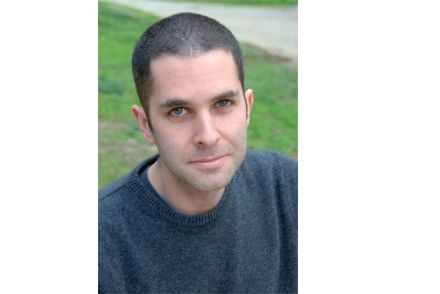

Tom Rachman’s debut novel The Imperfectionists is a sharply observed, beautifully characterised look at the employees of an international newspaper based in Rome.

You have worked at various newspapers, including as a foreign correspondent in Rome and as an editor at the

Using what I’d observed during my years in journalism, I sought to invent a realistic paper and to offer a peek into the workings of the international media – the flavour of a newsroom, the ambitions of reporters, the lives of expatriate editors. That said, each character and story was invented, and the paper does not represent a particular publication.

The book is told in the voices and from the perspective of various employees of the paper, from foreign correspondents, to sub-editors, to the editor-in-chief and the chief financial officer. Was it challenging to capture all those unique voices and bring them together to tell one wider story – the story of the paper itself?

Weaving the strands into a single novel presented certain challenges: for example, ensuring that all characters remained animated in the reader’s mind even after they had stepped from the spotlight of their own story and into a supporting role in another’s. Also tricky was ensuring that the tale of the paper itself be captivating, without the hook of a single leading protagonist. To manage this, I tried to build a newspaper that was not simply an organisation but the sum of the unusual characters who produced and read it – just as a real newspaper is.

This is a very funny novel, though it is often also deeply sad. What appeals to you about this combination?

I suppose it’s my world-view. Life is so often sad and maddening and unjust – and then it’s over! If we responded to this with bitterness alone, we would be a uniformly grumpy and unproductive species. But we have humour thankfully. I have always loved stories that express this – the humour that arises precisely because life is sad. Small, nervous people pretending to be tall and bold: it is sad and funny at once.

The Imperfectionists

I do. So many mornings I have spent getting my fingers inky, devoting far too long to the newspaper pages. This isn’t to say that I adore everything about papers. Indeed, one of the pleasures of the media is hating it. My father – a devout newspaper reader – spends much of each day denouncing the publications that he nonetheless buys without fail. I’m truly sorry at the decline of newspapers. Life won’t be the same without them.

The book begins with a 70-year-old foreign correspondent, well past his prime, hopelessly out of touch with new technology and in professional freefall. Is he a metaphor for newspapers themselves?

He could be interpreted that way, and it’s certainly true that newspapers are similarly in freefall. But his problems extend beyond technology, including sexuality, his sense of usefulness in the world, the cost of his past egotism, his regrets. His case is more that of an ageing striver who can’t bear to see strength abandon him. And in this, perhaps, he may share something with newspapers.

Many of the successful characters in

Yes. The ambitions that churned through journalism – my own included, at certain times – were not those of contented souls. Every scoop, every page-one story, every promotion produced a shiver of triumph followed by a gradual return to the previous state of dissatisfaction. Then ambition rose again, insatiable. I found this effect fascinating in myself and in others, and hoped to depict it. To be clear, I do not think that professional aspiration and personal happiness are exclusive. Only that ambition risks feeding just itself, offering little to its host.

Many of the chapters in the book, which also work as self-contained stories, unfold in unexpected ways. I often felt sure I knew where a story was heading, only to be surprised when it didn’t reach the conclusion I imagined it was leading up to. Was this an effect you worked for, in writing the book?

An ending produces a note that is left ringing in the reader’s ear, a tone that resonates backward through all that happened in the story. If this final note is the same as that which sounded throughout the story, then the tale risks blandness – you may think, Why did I bother? If it’s wildly dissonant, however, that’s worse, since it undermines the credibility of the story. What I sought were endings that deepened the reader’s understanding of what preceded, illuminating the characters suddenly and starkly, so that the story ends not with a full stop but that it reverberates afterward.