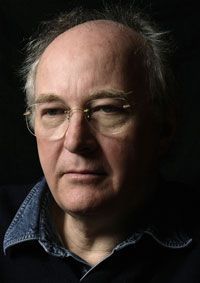

Philip Pullman is one of the world’s highest profile atheists. His

,

The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ

.

Jo Case spoke to him for Readings.

You have been much celebrated for your anti-religion trilogy, His Dark Materials, and recognised as an outspoken atheist. What made you decide to tackle the story of Jesus in this book? What questions are you hoping to raise or stir?

I’m always a little sorry when people reduce His Dark Materials to an anti-religion tract – not that you’ve said that, but people do. I’d hoped it was rather more than a tract of any kind. Is it anti-religious? Not at all. What it is is anti-church, or to be more specific, anti-organised religion. Religion is something that all human societies, and most human beings, do. We can’t help being religious; it’s wired in. What I’m passionately against is letting religious organisations get their hands on political power. And I was attracted to the story of Jesus because I saw in him a great (and human) revolutionary figure whose teachings were taken over almost at once, and, little by little, hidden from view, while a separate and divine figure – Christ – was invented to form the central object of worship. I hoped to make the difference between these two beings a little clearer than it was.

You’ve said that Christianity is ‘in the nerves of my brain and fibre of my heart. It is what made me.’ Do you think the fact that elements of Christian culture are so integral to who you are contributes to you being such a passionate critic of Christianity?

I’m sure that’s right. It’s why William Blake, himself a Christian by upbringing, was able to demonstrate in ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’ that Jesus broke all ten commandments. You need to know the stuff to argue with it. It has to move your imagination. That’s why I haven’t written about Islam, for example, about which I know very little, despite the sneers of some of my critics, who would like to be able to call for my assassination themselves, but lack the courage to do so outright and instead try and draw my existence to the attention of the biggest playground bully of the moment.

You say that St Paul ‘wasn’t interested in Jesus, he was interested in Christ – in the God part, not the man part’. It seems that in this book, you’re interested in ‘the man part’, and how the telling of Jesus’ story created ‘the God part’ – in a very calculated manner. What attracted you to this aspect of the story?

Well, he’s a very attractive figure. He was one of the greatest storytellers of all time (and of course that interests me) and he had an unparalleled gift for making phrases that linger in the memory with the force of revelation: whited sepulchres, the mote and the beam, that sort of thing. I couldn’t resist him.

The mysterious Stranger who bids Christ to write (and embellish) Jesus’ story to build a basis for the church asks him, ‘which is better… to aim for absolute purity and fail altogether, or to compromise and succeed a little?’ This seems to be the consummate self-justification of a politician. Is that Christ’s role – the politician half of the church? Or is it more complex than that?

That’s pretty well what it is. But I always hesitate before confirming or denying a particular reading of one of my books, because my reading ought to have no more authority than anyone else’s, though it naturally seems to have. I believe in the despotism of writing, but the democracy of reading. Once the book is out of my hands and in the public’s, I don’t own its meaning any more. It’s open to anyone to put forward an interpretation. If they do so, however, they must be able to defend it by reference to the text itself, and not to any private knowledge or secret information – which of course I must seem to have, because I wrote it: which is why I hesitate.

In your book, Jesus says: ‘Lord, if I thought you were listening I’d pray for this above all: that any church set up in your name should remain poor and powerless, and modest. That it should wield no authority except that of love.’ What do you think Jesus the historical figure would make of the church that was built in his name, based on the story of his life?

His own phrase that I quoted above – whited sepulchres – comes to mind. When you consider the poor, wandering, hand-to-mouth figure of this peripatetic prophet and healer, who had no place to lay his head, and you compare him with the fantastic and unimaginable wealth and splendour of the Pope in all his glory and his power, what can you do but…well, shake your head?

The power and function of storytelling is at the heart of your book. ‘In writing about what has gone past, we help to shape what will come.’ How does this relate to the Bible’s role in shaping history, along with Christianity itself? And how does it relate to your view about the role of stories in general within our culture?

Stories do have a huge influence on us. And the storyteller has a corresponding responsibility. But the storyteller’s primary responsibility, as I’ve said before somewhere, the one that trumps every other, is to the story itself. He or she must follow not the will, not the conscience, not the political or environmental or religious concerns of the moment, but the imagination only, because only the imagination will make a story live.

You’ve said religion stems from ‘our desperate need to account for and give an explanation to things’. Do you think this story – along with more straight fact-based approaches to separating the historical Jesus and his life from the religious figure and his supposed miracles – are similarly feeding a need to ‘account for’ and explain things?

I don’t know what they feed, or might feed, because I don’t consider the effect a story will have. I don’t consider the audience at all. If I did, I’d have to stop writing altogether. The only hope I’ve expressed about this book is that it might draw some readers to look at the Bible and see where I’ve changed something, or left something out, or put in something new, or transmitted it without alteration. I hope they’ll read the Gospels for themselves, and see all the contradictions, the ambiguities, the inconsistencies and the difficulties the church tried for so long to conceal from the ordinary worshipper, by keeping the text in Latin and persecuting those who worked to put it in the vernacular (look at the horrible death of William Tyndale). I hope they’ll see the things that simply don’t get noticed in the ordinary course of a church year, when the story follows the liturgy and not the Gospels directly. Read the Bible! That’s the ‘message’, if there is one at all, of this book.