It was a dark and potentially stormy night as I waited at the bus stop on the palm-treed traffic island at the corner of Denham and Fletcher streets in South Bondi – darker than normal, because of a power blackout. The blackout hit as I was getting ready to sneak out of my parents’ flat at Tamarama for the two-mile trek to the Bondi Lifesaver. I would often sneak out, sometimes to see friends, many times to go to the Lifesaver or the top-floor disco at the Squire Inn. I’d grown expert at putting on make-up in the dark, so the blackout didn’t slow my preparations. That night, the lightless road and the heat and humidity formed a sultriness I loved, as a sixteen-year-old self-styled rebel. The smell of the ocean, my own sweat, a thunderstorm looming – it made the anticipation of a night at the Lifesaver even more delicious. That place was a haven to me, the dangers of being a girl alone (except for the danger of getting hit on by a boring surfie) never crossing my mind.

The Lifesaver was covered in layers of band posters. In my imagination there were bands on every night. It felt like I was there most nights too. The DJs and bar staff never questioned my age; I’d been getting into pubs since I was fourteen. Long, low velvet lounges – dark red, I think, but the space was so dimly lit I can’t be sure – framed the room in front of a massive tropical aquarium. A timber bar stretched along the eastern wall, illuminated by the reflected light of the mirrors and the astonishing rows of bottles behind. Some nights that bar turned into Angus Young’s runway, an appendage to the main stage from which he would be lifted and carried away on Bon Scott’s shoulders, Angus not so much duck-walking along the length of the bar as duckstomping, like an overwound mechanical toy, hair and sweat flying.

That night at the Lifesaver, unable to hear anything above the band – AC/DC, though I had no idea who they were – I squeezed my way through the crowd. Our bodies cooked up a sweat soup, eager for lustful encounters. In that atmosphere I could have two or three mini-obsessions a night, acted out with Olympic-standard stalking and flirting. I wanted to meet the singer, Bon.

I hung around after they finished and it wasn’t long before Bon emerged from the band room to lig with the punters. I waited till he had a break from the yobbo hair parade and said hello. He was instantly charming, even before the dental work. It was late and I said I had to go to work the next day. He asked me for my phone number and said he’d call tomorrow. Sure, I thought.

It was 1976. Our bell-like telephone sounded: ring-ring … ring-ring … (pause) ring-ring … ring-ring. ‘Yes,’ Mum answered, ‘she’s here, just a minute.’ I clutched the receiver. ‘Hello?’

From the other end, a gently worn voice: ‘Hi Helen, it’s Bon. From last night.’

My heart was thumping but we managed to arrange for Bon to visit me at work the next day. It was his suggestion. Sure, I thought (again). But the next day there he was, standing on the step in front of the jeans shop where I worked, smiling and looking like the perfect ruffian. I was captivated. I loved the bad-boy look and Bon oozed it. Forget my Olympic-standard flirting; this guy was competing at the intergalactic level, and winning. This is my memory of Bon: charming, gentle and magnetically dangerous-looking. He was thirty and I was sixteen. It was lust at first sight and our polite courtship lasted as long as it took for night to fall and me to get back to the Lifesaver.

I spent quite a few nights with Bon at the Squire Inn, at Bondi Junction, where we laughed about a squished cockroach dangling from the sprayed concrete ceiling that he claimed to have dispatched the previous day by hurling a Yellow Pages at it. One evening I stood waiting at the lift in the Squire’s foyer. The doors clanked open and there was Bon, a girl under each arm. My face must have said it all because he announced, ‘Don’t worry. I’m just taking these girls over to the Lifesaver. I’ll be upstairs in a while.’ Big cheeky grin. What was I to do? Wait, of course.

I took days off work to wait in his room at the Sebel, feeling privileged to be left alone with his beautifully handwritten notes and lyrics. When he was pleased with his work, he’d rewrite the words in capital letters on a fresh page. So neat for a rock star! He also smelled nice. Probably of high-octane pheromones. Sitting in bed at the Sebel late one morning, I watched him get ready for the day, primping to the sound of Donna Summer’s disco hit “Love to Love You Baby” while gargling Coonawarra red and honey (for the vocal cords). His body was compact and muscly and felt like the perfect fit when we embraced. Which was often. He loved wearing sleeveless singlets because he said they made his muscles look bigger. Maybe he was vain. But show me a lead singer who doesn’t have an ego.

One night at the Lifesaver, the band played to a packed house and I was backstage, thrilled to be one of the special few allowed into that tiny, stinky, scuzzy band room. I could see only part of the stage but I knew something was wrong as one by one the guitars, then bass, then drums plonked to a halt. Next thing Angus was hobbling off, bleeding like crazy from the legs, the rest of the band dealing with a commotion at the front of the stage. Someone had smashed a glass and gouged one of Angus’s shins. A call went out for Angus’s aunty to come and help. I don’t remember everything from that night, it was always exciting though, what with groupies (not me of course) rooting roadies, random urinating and general delinquency.

In some ways Bon seemed like an older brother to Angus. He once took me to the Youngs’ home in Burwood to celebrate Angus’s birthday. The house was old-fashioned, not at all flash. As a birthday present, Bon gave him a T-shirt with ‘Here’s Trouble’ printed on the front – the shirt was tiny. Angus said, ‘He gives me the same T-shirt every year,’ and I sensed it was a welcome ritual, then we sat and listened to Billy Connolly records, Bon laughing at the Scottish banter and me able to decipher barely a word of it. I felt so happy to be doing something ordinary with a guy I’d really only spent time with at gigs or in hotels.

Bon used to tell me about his former wife and other women who were important to him. I felt he liked talking to me just as much as the other stuff we got up to. Sometime in 1976 the band went overseas. Bon wrote me a long letter, but by the time I received it I had moved in with a new boyfriend. I ripped up the letter, worried it would cause problems if I tried to hide it. What a dickhead I was. I should have kept that letter. It was a lovely, warm, descriptive, kind letter, written on blue airmail paper in Bon’s everneat handwriting.

Later that year AC/DC returned triumphant to Sydney, and I wanted to be at the airport to see Bon. He might have even asked me, in that long-gone letter, to be there. Using my well-honed sneaking-out skills, I dressed in a white skirt and jacket pinned with a big, fake red rose. God knows how I reached the airport – at that age I thought Mascot was another country – but I got there, and waited, while the press interviewed and lauded the band. I waited and waited but I had to get to work. It was easy to be sacked back then. At some point I must have decided it wasn’t worth it. What would I do if Bon wanted to start seeing me again? I was well and truly in a relationship by then and didn’t want to hurt anyone, least of all myself. I had just turned seventeen. I looked beautiful in my white suit and red rose but something made me turn around and go without welcoming Bon home to Sydney.

Bon and me were a long time ago. There’s no way I can be sure of dates or specifics of our brief encounter. But the sense of him is still so strong that it is easy and covertly arousing to think about.

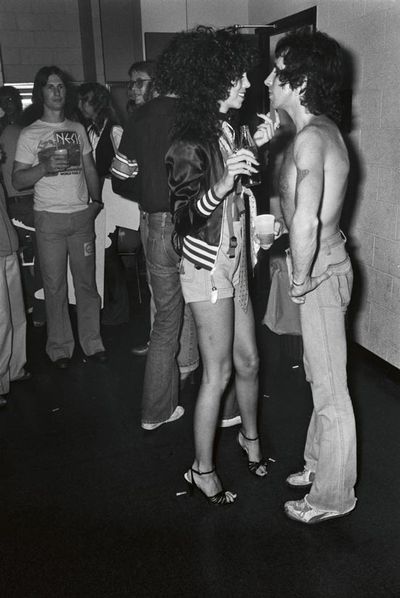

Alongside Helen’s essay