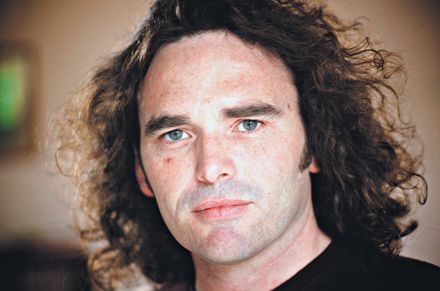

Joel Deane is well known in literary circles as a poet: his collection Magisterium was shortlisted for the prestigious Melbourne Prize for Literature in 2009. He has also been a journalist and a political speechwriter (for Steve Bracks, then John Brumby). Jo Case spoke to him for Readings about his eagerly anticipated, utterly engrossing debut novel, The Norseman’s Song.

This is a wildly original novel – combining the confession of a nineteenth-century whaler with those of an ex-con taxi driver and a dying former journo in contemporary Melbourne, all of their lives steeped in violence. Where did your inspiration come from?

The genesis of The Norseman’s Song comes from a shred of family history and a meeting I had when I was 15 years old. The history is that one of my forebears was a Norwegian seaman who jumped ship in Melbourne in the nineteenth century.

The meeting was with a 95-year-old relative. This old man was the size of a redwood, walked like Frankenstein, had fire in his eyes, ranted about the decline of morals, yet had, I knew, fathered at least one child out of wedlock. I loved how cranky and contradictory that rellie was and decided to write an imagined history about a Norwegian with that old man as the physical template.

At the time, I was 15 and knew I didn’t have the chops or the depth of experience needed to write that book. That’s why I started working as a copyboy in a tabloid newspaper when I was 17 – to season myself. Along the way I held onto what became a 20-year-long daydream about the Norseman – influenced by my experiences as a newspaper journalist and the taxi-driving stories of my father and grandfather. Other stories and experiences fed into that daydream, such as the one about a Turkish soldier’s head that was found in Echuca decades after it was souvenired by an ANZAC. Or the one about the exorcist I once knew who stood trial for the accidental killing of a woman. There are too many to list.

By the time I sat down to write the first draft of The Norseman’s Song that daydream was closer to a nightmare – and it was a nightmare I’d never told anyone about. Maybe that’s why the first draft came out in 33 days straight. Telling aloud for the first time a story that had been internalised for so long was an incredible rush – it’s the closest I’ve come to an out-of-body experience.

The novel has an intimate yarn-spinning quality that draws the reader in – like (the very different)

Bruce Springsteen once said that he wanted his breakthrough album, Born to Run, to explode in people’s stereos. When I was writing The Norseman’s Song I was fired by a similar ambition: I wanted it to go off like a hand grenade. I wanted it to be a fable like no other. I wanted it to tell a story about men and violence and the lies we tell to rationalise our lives, our beliefs and our histories. I wanted it to be bristling with voices and stories. I wanted it to drag people along for the ride whether they wanted to go or not. The best way to achieve all that was to tell a great story.

My influences were too numerous to list. The ones that particularly inspired me, though, were The Icelandic Sagas, Edgar Allan Poe’s The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, Arthur Conan Doyle’s A Study in Scarlet, Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, and, of course, Joseph Conrad’s Lord Jim and Heart of Darkness.

Another influence dated back to my days as a journalist. I was struck my the way people talk about incidents – the way they talk around events and come back to them, as well as their verbal ticks. I wanted to write like people think and talk.

This is your first novel, but you’ve also written journalism and – most notably – poetry (which is evident in your prose, particularly your imagery). Do you think your experience in these other forms influenced the way you approached writing a novel?

Definitely. Writing a novel is very different to writing a poem. You need the feel for language as music, which I developed through poetry, to make a novel fly creatively, but you also have a story to tell and, if you want to tell that story, you need the grunt to climb a mountain of 70,000 words – or more.

Poetry is the impetus of all my creative writing, but my fiction is equally reliant on the muscles I’ve developed through years as a reporter, editor, producer and speechwriter. In other words, I know what’s required, physically, to write 10,000 words a week.

The other thing I’ve learned through poetry and speechwriting is that writing is performance. To perform properly, you need to train by reading widely, you need to practice by writing constantly, and you need to improve by revising and editing ruthlessly.

There’s a lot in this novel that is confronting – your contemporary characters are racist and misogynist, shockingly so at times. Were you using these characteristics to comment on our society, or were these merely characteristics you thought these types of characters would have?

I didn’t setting out to write archetypes or deliver a message. What I was trying to do was understand some of the forces that make our nation what it is, for better and for worse. I’m talking about violence, I’m talking about mateship, I’m talking about racism. I wanted to write about an underbelly of contemporary Melbourne through the taxi driver, Farrell. I also wanted to go back to the limits of lived or oral history through the old journo, Bob, as well as inventing a mythic history through the Norwegian.

The only rule I set myself during the writing was to not flinch from the ugly stuff. I loath boutique fiction – the kind of books that are more about the novelist wanting to be loved than trying to tell a story that’s never been told before. I’d like to see more novels be true to the meaning of the word ‘novel’.

The taxi driver and his passenger, ‘Bob’, take us on a meandering night-time tour of Melbourne’s suburbs (Doncaster’s ‘houses too polite to tell apart’, Footscray flats, the oft-disparaged ‘Lego-land’ of Caroline Springs). What was the idea behind this tour of Melbourne and surrounds?

The idea behind the tour of Melbourne is that Bob and Farrell’s taxi ride is an odyssey. At the beginning, they’re both lost: Bob is searching for a way to end, Farrell for a way to begin again. The places they go and the people they meet along the way are part of that odyssey. You could say it’s an odyssey of Melbourne’s modern and mythic history. As for Doncaster, I live there and couldn’t resist giving my suburb a walk-on role.

Both ‘Bob’ and the Norseman of the title observe the intimacy of killing (the Norseman says ‘it binds the killer to the killed as surely as consummation binds the groom to the bride’). How integral is this idea to the book?

I’m the kind of person who can’t sit through violent movies – once I made it out to the foyer of a cinema before I fainted. Why, then, have I written a novel that, at its heart, is all about violence – not just acts of violence, but the reverberation of those acts? Hard to say. All I know is that violence both distresses and obsesses me. I guess I’m trying to understand why we do the terrible things we do.