Michelle Law recalls her first reading addiction, escaping into

Back in the early thousands, Christopher Lee was interviewed about his role as Saruman in the Lord of the Rings films. ‘How did you prepare?’ asked the journalist. Lee replied that he did little preparation. He was already familiar with the character from re-reading the trilogy every year. I allowed Lee’s response to sink in. Wouldn’t you get bored of reading the same books? What could you gain from those readings? And would no 12-page Elven song stop you?

I could only conclude that Lee had lost his mind in his old age. Back then, I didn’t realise that Lee – an expert fencer, multilinguist, Dracula, former Nazi hunter and past Guinness World Record holder for ‘tallest leading actor’ – is a badass who should be taken seriously. Because sometimes, a book will come along that changes your life forever.

I’ve read Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë countless times since discovering it six years ago. Over time, it has become gospel to me, possibly because I’m a religionless toad, but probably because it’s a damn fine book. It’s special to me because it came at a time in my life when I needed it most, and because it helped me understand the significance of books and reading.

As a teenager, I saw books as escapism. I grew up on the Sunshine Coast, something I’d recommend to any youngster with a penchant for the sun, surf and tank tops, and not for any youngster who is Chinese, myopic and bookish, like me. I was different to my peers in every way and I desperately wanted to fit in. I tried swimming (failed) and buying Billabong board shorts (failed). I wanted to go to parties where I could wear make-up and kiss boys, but I was prohibited from attending any due to my mum’s belief that they resulted in drunkenness, lewdness and pregnancy. (To her credit, most of these assumptions were true.) It was, she assured me, best to stay home. She needn’t have worried, as throughout most of my adolescence I was a willing prisoner. At the start of high school, all my hair fell out from alopecia. I had few friends, I was bullied, and I couldn’t bear being stared at when I left the house. So I was content to stay indoors and live vicariously through books.

At night, after Mum fell asleep, I would make peanut butter on toast and some black tea and sit at the kitchen table under the brightest light and read until dawn. I loved the different worlds in the His Dark Materials trilogy. Harry Potter was important to me because I was around the same age as Harry upon each book’s release. The Virgin Suicides reinforced my growing sense that the suburbs were both thrilling and oppressive. Maus taught me history when I struggled to understand it in dusty tomes. I loved books, but I didn’t feel much towards them besides the dull recognition that they were entertaining. To me, they only helped pass the time.

were literally giant eggs – handed me a faded library copy of

Jane Eyre

and told me to read it. It was a withered paperback with torn and yellowed pages. On the cover, a cartoon Jane rendered in purple and teal stood in a dark hallway illuminated by candlelight.

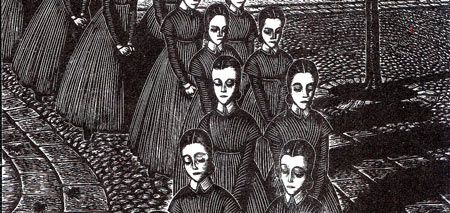

I practically disappeared during the fortnight it took me to finish the book. I spoke little. I moved little. I forgot to eat and drink. Mum would make hourly stops at my bedroom door to check that I was still alive, bearing nuts and juice for sustenance. I read Jane Eyre on the car ride to and from school, and on trips to Woolworths on the weekend. When I brushed my teeth, I held my toothbrush in one hand and the book in the other. When I flossed, I held the book down with my foot on the basin. All that mattered to me at the time was Jane and what happened to her. And as I read, it became apparent, however vaguely, that I was growing up.

In Jane, I saw traits that I admired and coveted. Here was a strong, independent, kind, intelligent woman who persisted despite being mistreated, friendless and plain. I liked that she was an outsider with a personality and sexuality, and it was because of these things, and not despite them, that she found happiness. It was important to me that she stayed true to herself, and that others valued this quality in her. As a 17-year-old with all of my frustrations and vulnerabilities seemingly magnified and acutely felt, I clung to Jane Eyre like a beacon of hope. I was astounded that a stranger who lived centuries ago had created someone with whom I could empathise so profoundly, and moreover, that there were readers who had lived and died before me who felt the same way. Jane Eyre showed me that writers could do magic things: they could make you feel less alone.

At present, I own four copies of Jane Eyre. There is one for reading (a Vintage Classic), one to lend (a Popular Penguin), one to treasure (a Random House hardback with engravings from the 1940s), and one to bring to the toilet (a shabby Reader’s Digest edition I found at a Lifeline Bookfest). I read many different authors and genres each year, but time and time again I find myself returning to Jane Eyre. Each re-reading draws from me new responses to characters and events; the book acts as a centre point for who I am and how I am changing.

I have no idea why The Lord of the Rings is important to Christopher Lee, but I like to think it’s because he connected with the story so strongly that when he read it he spoke little, moved little, ate little and spent most of his waking hours thinking about it. I like to think on how we return to these books like a security blanket, or the company of a good friend. We seek them for comfort, familiarity, insight and the reassurance that we aren’t as alone as we once thought.

Michelle Law is a Brisbane-based writer and screenwriter whose work has appeared in