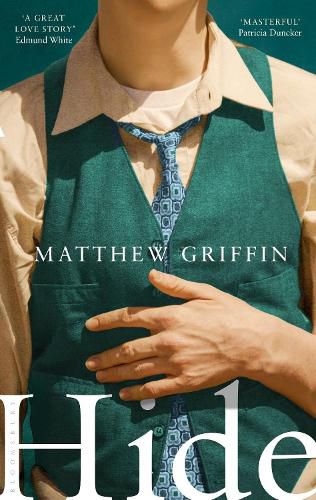

Q&A with Matthew Griffin, author of Hide

American author Matthew Griffin chats with our own bookseller Jason Austin about his powerful debut novel, Hide. (You can also read Jason’s rave review of the book here.)

First of all let me say congratulations! I loved Hide so much, not just for the exquisite writing but also for the subject matter. Your novel tells the story of two men, Wendell and Frank, who meet and fall in love at the conclusion of WWII and follows them into old age. Society is often attracted to stories based around youth culture, and the gay community is no exception so it’s so refreshing to read a story about mature gay people. What drew you to writing about an older same sex couple?

Thank you so much for the kind words! I really appreciate them. Writing about an older couple was the original impetus behind the novel – I was quite close to both sets of my grandparents, and I saw them at the ends of their lives struggling to take care of each other as their mental and physical health declined. It seemed like just the most tragic thing – the way you can sacrifice and compromise in order to build a life around this one beautiful person, against all the odds the world throws at you, only inevitably, in the end, to lose them. From there, I started thinking about what it would have been like to have done the same things as a gay person in the 20th century, with all the added dangers and sacrifices that would have entailed. It seemed like a story I hadn’t read before, and one that felt important to tell.

Here in Australia, there has been a protracted debate on same sex marriage. Although your novel isn’t overtly political, were you inspired to write Hide with the current subject of marriage equality in mind?

I was very careful not to be explicitly political while I was writing the book, but of course everything is political in its way, and marriage equality was definitely on my mind while I was writing Hide. I started writing it in 2011, and the years after that were the years when the movement for marriage equality here in America was really intensifying, and when victory started to seem possible. So all the issues attendant to that were in my mind, and some of them – like hospital visitation rights and power of attorney – do make their way into the novel, as subtly as I could possibly manage. And ultimately, though the book isn’t explicitly political, Frank and Wendell’s relationship could be seen as an argument for the legitimacy and beauty of LGBTQ relationships.

Did you have to do a lot of research around this novel, particularly relating to the generation of gay men that Wendell and Frank represent?

I did do quite a bit of research in order to understand what it would have been like as a gay person during that period – particularly the decades after World War II, when there was a bit of a moral panic in America about the habits some of the boys had picked up overseas, all of which funneled into the McCarthy era, when homosexuality was consistently linked to communism in public debate, and both the Federal government and local authorities became much more draconian in their enforcement of laws that criminalized gay people. In the process, I actually found an article about a series of arrests in my hometown of Greensboro, NC during the late 1950s, during which over 30 gay men were arrested, many of whom went to jail for 20 years. The challenge then was to incorporate all of that into the narrative in a way that didn’t seem too heavy-handed, or like it was trying to teach some political or historical lesson, so I focused on using that knowledge to try to evoke the feeling of prolonged, pervasive anxiety and fear in Frank and Wendell’s lives.

Are the two men actually based on real people?

In a lot of ways, Wendell – in my mind, at least – combines a lot of characteristics of my grandmothers, while Frank is sort of a combination of my grandfathers. There are no one-to-one correlations, and I just pulled details from my grandparents’ lives as they came to me. Like Wendell, one of my grandmothers was always cooking, and one of my grandfathers fought in World War II like Frank did, though my granddad was in the Marines, not the Army. Their voices are also very much reproductions of my grandparents’ patterns of speech; writing in Wendell’s narrative voice was a lot like listening to them talk to me again, which was what carried me through a lot of the process.

Wendell’s occupation is as a taxidermist. There is quite a lot of the practice and its related techniques in the book. I thought this was brilliant as the art of taxidermy has always fascinated me. What made you decide on this craft for Wendell?

Partly it was just because, like you, I’ve always been fascinated by taxidermy. I think that was probably the first thing that drew me to it – it seemed like a strange thing that would be fun to learn and write about. But as the book progressed, it made more and more sense to me, because taxidermy would be a profession that Wendell could occupy which would help him maintain their seclusion, since he wouldn’t have coworkers, and I thought that even his customers wouldn’t ask him a lot of personal questions, because of the way many of us tend to look askance at people whose professions steep them in death. And, beyond that, it seemed to mirror the broader conflict of the book. Taxidermy is ultimately about trying to preserve a kind of life in something from which that life has already gone, and throughout the book, Wendell is struggling to keep Frank healthy and hold onto the man he once was, when that man is inevitably slipping away.

There is a part of the novel, near the end which had me squirming and reading through my fingers. Without giving anything away, it’s a little confronting, but marks a very important moment in Wendell’s realization of what is happening to Frank. Have you had much feedback from other readers about this ‘incident’?

Oh, man, have I gotten feedback! I hear about that section more than any other. I know some readers have gotten to that point in the book, thrown it down in anger, and refused to come back to it. But I think most people understand the significance of that moment and while it had to happen. And it’s certainly a passage that I did not relish writing – at one point, very late in the process, I couldn’t bear it myself and I tried to rewrite the last quarter of the book so that it didn’t happen, but when I pulled it out, the rest didn’t quite hold together, and back in it went. So I certainly understand why some readers might be enraged by that moment, but also I think that the subject matter of the rest of the book – oppression, isolation, aging, mortality – isn’t exactly for the faint of heart either.

There is a long tradition of great writers from the American South. Anne Tyler and Ron Rash are two of my favourite authors from your area of the US. Do you think that there is something about the Southern sensibility that encourages great storytelling?

I think there must be, though I wouldn’t presume to be qualified to pinpoint exactly what that something might be. But I do think there’s a strong culture of oral storytelling here in the American South. I live in New Orleans right now, where that culture is particularly vibrant – people here love to sit around and tell each other stories. I mean, even if they just met you, they’ll tell you all kinds of things about themselves; it’s really one of the most wonderful things about this place, and although that culture is more intense here, I think it exists throughout the South – or has existed. It’s hard to say how that may change as technology continues reshaping our lives. The South has also been the place of the most intense, brutal injustice in our country, as well as the place of our bravest resistance to oppression. Many of us grow up here steeped in a sense of that very dire conflict and its complex, manifold moral consequences, as well as with a feeling of how the past shapes and suffuses the present – all of which lends itself, I think, to great literature.

How long did it take you to write Hide and what challenges or victories did you have in writing the novel?

It took me just about three years, from start to finish, although most of that was revision. The first draft only took me three months, and it was the most blissfully fun writing experience of my life – I often had the feeling of the words just moving through me, as though they were coming from some other place. The biggest challenge, then, was in revising, because as it turns out, those passages that seemed like they were spontaneously emerging perfectly formed were actually a complete mess. So I went through draft after draft, trying to cut away any scene or storyline or sentence that I didn’t love, that didn’t feel absolutely alive. I sort of adopted the opposite of the ‘kill your darlings’ mantra and killed everything but my darlings – and, by the end of the fifth draft, I was so tired of reading my own sentences that the threshold for becoming my darling was pretty stringent.

What are you reading and / or what was the last book that you enjoyed?

I tend to read fiction almost exclusively, but I also have a real weakness for true crime, so right now I’m reading Robert Kolker’s Lost Girls, about the victims of a serial killer in Long Island who is most likely still at large. I’m really enjoying it so far. It’s beautifully written and compassionate – and terrifying, of course, which is how I like it. I also recently read Stuart Nadler’s new novel The Inseparables, which I absolutely adored, about three generations of women at a moment of upheaval for all of them. It’s funny and sad and smart and big-hearted: all the things a great novel should be.