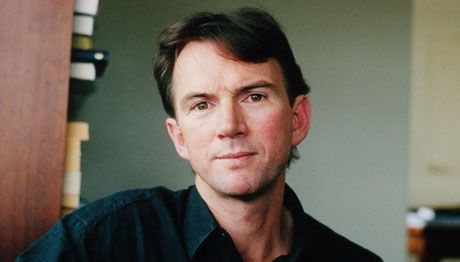

Peter Rose is one of Australia’s foremost literary figures – well known in his long-running role as editor of Australian Book Review and as author of the bestselling memoir Rose Boys and Miles Franklin longlisted novel A Case of Knives. Jo Case spoke to him for Readings about his latest novel, a wickedly funny satire set in the literary world, Roddy Parr.

In

Yes, as with nearly everything I write – unfinished business. I knew I wanted to write about a very similar world, bridging literature and politics and the performing arts – so why not revisit the Anthem world, examining my characters from different perspectives? All I had to do was to give Philip Anthem, the former PM, a literary brother, and hey presto! I was very pleased to be able to reacquaint myself with Julia Collis. All my life I’ve been drawn to serial novels – or romans-fleuves – with their gradual accretions. And yes, I do have plans for more.

Your book features some wonderfully complex characters who are perversely likable – like Julia Collis and the famously reclusive, acerbic (and contrary) world-renowned author David Anthem. They’re great fun to read – were they fun to create? And as a literary insider yourself, did you draw on any real-life observations or characters?

Not real people as such – that would be limiting, not to mention presumptuous. During my 20 years in publishing I’ve worked with some real characters and desperadoes, but no one quite as diabolical as Julia Collis. She makes me want to take up smoking again and drink more cocktails. But I can’t deny borrowing phrases and mannerisms and predicaments from people I’ve known. That’s all a writer can do – the magpie life.

David Anthem says, ‘Fiction’s like play-acting. People don’t realise … What we crave is other lives, other fates, respite from our own shrivelled selves.’ Do you agree with his view? Do you enjoy the ‘play-acting’ aspect of writing fiction?

I do think it is related to acting, to sheer make-believe, which is probably why so many novelists crave success on the stage, either physically or in a literary sense. Terrifying though fiction can be – with its responsibilities to embody characters, dramatise their lives, imbue them with plausible yet original psychologies, understand everything about them – the pleasures are quite addictive. Daunting it may be, but it’s also very playful, in the best sense – the lost sense.

The novel explores ideas of storytelling – in the form of gossip, media reports, biography and fiction based on fact – and how it shapes what we think we know about people and events. It reminds us that we need to be sceptical (or at least thoughtful) about what we read and hear. Was this something you specifically wanted to explore? What attracted you to these ideas?

Roddy, though clearly very bright, still behaves like a rather young man. He is guileless in a pretty threatening world, full of older characters who have been tested by life and who have acquired a kind of protective carapace. Roddy has such idealised notions about people. Now he comes up against masters of dissembling and evasion.

As well as being set in the literary world, the novel is littered with literary references, from anecdotes involving your fictional character’s friendship with the real-life Patrick White, to references to Henry James. Was this an aspect you worked to weave into the text, or was it an organic process? And did you have any qualms about mixing fact and fiction together (ie. Patrick White)?

It happened pretty automatically, without my fretting about the ethics of it. I’ve always liked the roman-à-clef. Alan Hollinghurst and Edward St Aubyn are just two British writers who have done this brilliantly in recent years. But we haven’t seen so much of this in Australia. As for qualms: writers have many responsibilities, but they also have a certain licence. Ultimately, though, my book is not about the heavyweights – it’s about two young people who are tested.

Roddy Parr, novice biographer, asks ‘who am I most obligated to – reader, subject, publisher myself’. Who do you think a biographer is most obligated to? Or does it depend on the book, the author, the subject and the relationships involved?

Years ago I wrote a family memoir, which made me realise what a complicated thing biography is, with the competing demands of art, ethics, fidelity, veracity, empathy, entertainment, etc. No wonder so many biographers end up disliking their subjects. Will Roddy fall out of love with David Anthem? We shall see.

Your novel makes some interesting observations about fame and how it can trick us into an imagined intimacy with public figures. It also looks at the divide between the public figure and the private person, and where these identities blur. Stella Anthem says to Roddy about her uncle, ‘To you David is an idea, a phenomenon, a library. To us he’s just an indispensable father or husband or uncle.’ What interested you about this subject?

Roddy is a thoroughly literary young man, with a profound respect for David Anthem’s writing. But he also allows himself to be seduced by Anthem and his set, and we’ve all seen what happens when the Great World decides to sport with an outsider.

Your day job involves the serious business of editing a literary magazine (

It seems to suit my particular imagination. I know we’re all meant to concentrate on one thing in this ultra-specialised world, but I like switching off and becoming someone else, working another part of my brain, as it were. That’s probably why I have always chosen to marry literature with a professional career of sorts. I’m not sure that isolation or specialisation would suit me.