Jane Sullivan

Jane Sullivan is bestknown to Melbourneliterature-lovers as thescribe behind the*Saturday Age’s

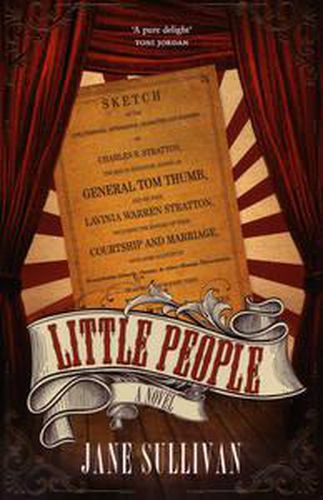

Don’t let the title of JaneSullivan’s new novelfool you. Little People iscrammed with big ideas andlarger-than-life characters,several of whom are famousmidgets. ‘I’d like people to have the sensethat they’re watching a wonderful show andthe curtain swings open and the characterscome on and they perform, and have someof that exhilaration of a live performance,’Sullivan says. ‘I hope it’s convincing … butI don’t mind if it seems a bit over the top.’In other words, even though real people andevents inspired Little People, Sullivan doesn’tlet history cramp her storytelling style.

More than a decade separates Little Peopleand Sullivan’s debut novel, The White Star(2000). That’s partly because she wroteanother novel in between: ‘It’s gone intothe bottom drawer now,’ she says. It’s alsobecause Little People ‘wasn’t easy to write. Ihaven’t found any novel easy to write.’ Sullivanis also a journalist – she writes a Saturdaycolumn, ‘Turning Pages’, in The Age— and she juggles the different demands ofwriting fiction and non-fiction by imagining she has ‘a little toggle switch’ in her head.‘Sometimes when the fiction isn’t going wellit’s a relief to get back to the journalism,’she says, ‘because there usually I feel I knowwhat I’m doing and it doesn’t take too longand I just need to find out x, y and z andthen I write the thing and I get paid and Isee it appear. And that’s nice, I feel like I’veachieved something, whereas the fiction candrag on for years. I never quite know whatI’m doing or whether I’m going to end upwith a proper novel at the end. It’s very hardto tell.’

Although The White Star is set in contemporarySydney, it shares some themes andpreoccupations with Little People. In particular,both books deal with fame, publicand private personas, the allure of seeminglyillogical ideas and celebrity adoption. ‘Tome they seem to be very different books,’Sullivan says. ‘Of course, there are thingsgoing on when you’re writing that you’renot even conscious of. There are themesthat pop up because you think about themconsciously, and there are also themes thatpop up without you even realising they arethere, but they somehow make their way tothe surface.’

In Little People, Sullivan takes two distinctstories – two different worlds, really – andmerges them into one raucous, chaotic,tense and deliberately melodramatic tale.There’s Mary Ann, the principal narrator,who must confront the stark reality of beingpregnant and unwed in 1870s Melbourne.And then there’s the spectacle of a troupeof P.T. Barnum’s little people, in Australiaas part of a world tour. From this, Sullivanconjures a novel in which performance andlife imitate each other in an energetic mix ofdastardly deeds, secret alliances, professionaljealousies, dubious science, and true andfalse love.

Mary Ann is, as Sullivan puts it, ‘the spineof the book’. She describes the little peopleand their entourage with the eye of aninquisitive outsider, except that, havingperformed an act of extreme bravery, shehas become an insider of sorts. The troupeemploys her, but they are mostly interestedin her because she is pregnant – Charles andLavinia Stratton, aka General Tom Thumband The Queen of Beauty, seem to have asolution to the conundrum of what shouldbecome of Mary Ann’s unborn child. ButMary Ann (and readers too) cannot be sureof the Stratton’s motives. For one thing,when it comes to babies, they have form.For another, Charles has some rather originalideas about conception.

While Mary Ann anchors the story, the colourfuland eccentric troupe shines brightest.‘There’s something in me that’s stronglyattracted to the quirky and the seemingly abit crazy,’ Sullivan says. ‘I don’t mean in thesense of psychotic or anything like that, justreally oddball … out of the mainstream. Ithink I’m attracted to those kinds of worldsand the people in them and what makesthem tick.’

What’s most interesting about the midgetsis not their size but their weird public lives.Sullivan humanises the Strattons, Lavinia’s sister Minnie and Commodore GeorgeWashington Nutt by allowing them to speakfor themselves. They interrupt Mary Ann’snarration to offer up their own perspectives– as does Rodnia, Commodore Nutt’s lessvertically challenged brother. These voices,labelled ‘sideshows’ in the book, so sparklethat they threaten to become the mainevent.

Charles Stratton is perhaps Little People’smost fascinating character. Sullivan pokesholes in Stratton’s puffed-up facade, imagininga rather sad but proud private man witha split personality. In a stand-out scene, aboy arrested in time reveals himself:My name is Charlie Stratton, and I amis thirty-two years and three months old;what the General used to be. The General he’s pulling himself together, he’s goingonstage to astound the Antipodeans withhis Napoleon. I’m four years old and I’mnot going anywhere. I have been four fora long time. You can’t see me, can you?I’m hiding. I’m good at hiding. I’m likethe boy in the picture puzzle. The boy inthe fork of the tree, the boy-shaped spacethe branches make. It’s kind of lonely uphere, but it’s the best place for me. Aslong as I keep still, you can’t see me.

‘I think he’s an extraordinary man,’ Sullivansays of the real-life Charles Stratton.‘It’s hard when you’re reading about him toget a sense of what he was really like. Whatyou’re reading about most of the time is theperformer and he was obviously quite a talentedperformer, although from all accountshe was not as talented as Commodore Nutt… At this stage of his life, Charles Strattonwas in his thirties, he had put on a lot ofweight and he seemed a bit tired and stiff, and not very convincing. He’d been performingsince he was four years old, which Ijust find utterly extraordinary. But growingup in that sort of totally artificial world andbecoming this celebrity, I think it wouldhave given him a strange sense of himself.’

Little People is greatly preoccupied withfame and celebrity. An example: whenLavinia first meets Mary Ann, she ordersher to kneel. While Mary Ann understandsthat she should pin Lavinia’s hem, Lavinialater explains, ‘This is what one does beforea queen, and I think I have been a queenfor most of my life, long before Mr Barnummanufactured me.’ The famous P.T. Barnumhovers over the story like a God-like creator.He trained the real-life Charles Strattonwhen Stratton was a young boy, andas Sullivan says, ‘that kind of oddity andfame at a very early age can distort people.The obvious example these days would beMichael Jackson.’ Sullivan points out thatAustralians in 1870 ‘didn’t have television orYouTube […]. When somebody like GeneralTom Thumb came to Australia, peoplewere absolutely thrilled to have a chanceto see him. He was this huge celebrity andhe’d come amongst us. No wonder they allrushed to the theatre and thronged into thestreets to see him and his troupe. It was anamazing event.’

Perhaps this is why Little People is suchthought-provoking entertainment. In goingback 140 years to observe celebritiesof another age, it invites readers to considercontemporary society’s fixation withcartoon-like characters such as MichaelJackson, Charlie Sheen or Lady Gaga. Andwhile Mary Ann is an outsider, so too arethe members of the troupe. They are Americans,sure of their prominent position in theworld, some of them world famous, who arestartled by Australia’s deserts and floods, itsover-excited crowds and even its inadequatemen: ‘All gape and guffaw,’ as Minnie putsit. Little People offers a fresh perspective oncolonial Australia and its peripheral place inthe world. In doing so, it also invites us tothink afresh about modern Australia.

Patrick Allington is the author of