Gregory Day

For Victorian novelist Gregory Day, his writing is inexorably linked to a sense of place. His three novels - all very different in form - are linked by their characters and setting, the fictional Victorian coastal town of Mangowak. Like the real-life coastal town Day calls his home, along Victoria’s Great Ocean Road, Magowak is being transformed by corporate cultural tourism.

In

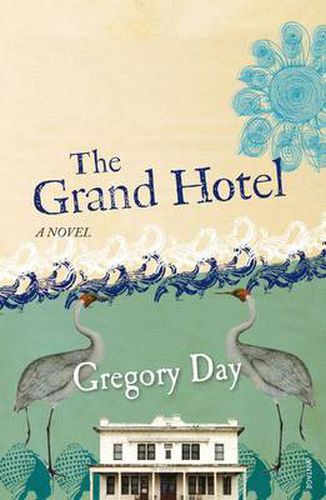

Lyrical though it is, Gregory Day’s writing takes its energy from contradiction. He loves to challenge stereotypes, to reconcile seemingly incongruous ideas. In his most recent novel, The Grand Hotel, he tells how a group of friends create a Grand Hotel in the fictional town of Mangowak. It’s a form of protest: the local shire has roofed a section of the creek and converted the only local pub into lifestyle apartments. On the face of it, this could be a macho tale about blokes and drinking; but this is a Dada happening, built on the site of the town’s first Grand Hotel. In this way, Day weaves ideas about Australian history, art, freedom and consumer culture into the fast-moving story of a small-town pub.

In Day’s Grand Hotel, the urinals play sound recordings, the burly barman is nicknamed Joan Sutherland, and the windows are boarded up to hide views of the sea. In the variety of their passions, the novel’s characters recall Dylan Thomas’s in the radio play, Under Milk Wood. It is characteristic of Day to make a poetic allusion part of the real world of his novel: in The Grand Hotel, a local amateur historian lives in an upstairs room and, while he sleeps, his transistor radio broadcasts the history of the town as it plays out in his dreams.

In his three novels about the fictional Mangowak, Day has invented miracles. He has developed this particular kind of realism to catch the character of postmodern Australian life. Day explains, ‘When I first started writing, I remember someone saying, “How can you have a story where Jane Austen sits alongside a game of country football?” Well, I can well and truly read Jane Austen at half-time at the football!’ For Day, these juxtapositions define the nature of Australian life. ‘I think Australia as an idea, rather than a country, is a driving force for a lot of us,’ he says. ‘It’s such an idea, and it was always an idea … The way that idea was carried out means we’re thrown into constant juxtapositions. In my life and in my interests – and this is true for all of us, I think – we’re living with a series of things, side by side, which, from some canonical view, would never be side by side. That’s what the colonies threw up. It’s a kind of realism, for me, to document that.’

The Grand Hotel takes its name from a 1920s novel and the 1932 film starring John Barrymore, Joan Crawford and Greta Garbo – at that time, the most expensive film ever made. It is characteristic of Day’s playfulness to name his story of a small-town Aussie pub after this early Hollywood extravaganza; Day’s playfulness typically works in the same way as his seriousness. He is fascinated by the combination of dream, practicality and self-delusion in everyday life, saying: ‘The Grand Hotel as a concept actually enshrines a theme where juxtapositions are born. It is a self-generating site, where people come from different places and meet. Across Australia, in the bush, are all these Grand Hotels, which are far from grand. That amuses me, going into towns and seeing those attempts at grandeur – like the explorer, Major Mitchell, making his self-aggrandising mimetic maps, the people were living in their imagination as they built those hotels, just as Noel and Kooka are living in their imagintion when they create this Grand Hotel in Mangowak.’

The Grand Hotel is Day’s third novel set in Mangowak – an imaginary town on the south coast of Victoria, set between the bush and the sea. Each novel has adopted a different narrative style. His first, The Patron Saint of Eels, was a fable. Ron McCoy’s Sea of Diamonds, though set in contemporary Australia, took the style of a nineteenth-century novel, while The Grand Hotel works as a picaresque mystery. What is consistent across all three novels is Day’s cast of characters and his lyrical, even magical, sense of place. Day’s point is that our habitual way of describing reality does not match the reality of our experience – in particular, how a familiar place holds the past and present, memory, myth and fact together.

This sense of place, more than anything else, defines the nature of Day’s realism, which in the nature of its inventiveness, has most in common with Calvino’s Marcovaldo and Furphy’s Such is Life. Day says, ‘For me, it’s a given that the past – and I mean, time prior to my birth – is in my present all the time. We don’t need to read T.S. Eliot to know about the relationship between the past and the future and the present. It’s in the nature of our biological and physiological set-up: we carry around time beyond our own span, all the time. When that type of existence is focused in one place, then the stories and the information, the feelings and inheritance, that we carry are embodied in sites. Those sites are not just spaces; they’re also temporal narratives.’

‘In the part of the world where I live, because my family has been there a long time … you just have to touch a thing, rub it a bit, for the stories to pour out. Now, that’s just a fact for everyone. And that sense of what we as humans are in that place is particularly rich now, I think, because we feel the places that we live in, the natural places, are in jeopardy.’

Noel and his friends create the Grand Hotel in reaction to the corporate cultural tourism that is spreading across Mangowak. Noel, who owns the Grand Hotel, and who tells its story, is an artist more interested in Dada than drinking. For him, the Grand Hotel is a modern-day attempt at spreading a new mutation of the Dada’s freedom virus: a creative, individual response to corporate control. ‘The Dada people were exemplars of that for me,’ says Day. ‘They were responding to the First World War: so atrocious, such a moment of industrialised culture, the industrialisation of death, with these machines set against the human figure in the landscape. The Dada response was, you can’t fight because they’ll just run you over. You can’t fight on their terms. You have to fight on your terms – you have to move the argument. For Dada artists, that meant unleashing what they called the freedom virus … It didn’t last long, it never could; because then it would have calcified. The corporates have always been deadly at colonising art for their own pathetic purposes. I think Dada remains an appropriate reaction to the blandness and scale of capitalism.’

Day’s achievement, in The Grand Hotel, is to make these ideas part of the life of his characters, and to make the life of his characters the force that drives his plot. Day’s first Mangowak novel, The Patron Saint of Eels, won the Australian Literature Society Gold Medal; he is one of Australia’s most popular writers. This success reflects his ability to bring different ways of thinking together. If The Grand Hotel is on the one hand a novel of ideas, it is, on the other hand, an engaging mystery. Day says, ‘That’s storytelling, making the page turn and the characters live. It’s like an engine: if there’s a bit sticking out here, it might be a great bit, but if it’s flapping around on its own, it has to go. I always think, is this a story worth telling? Is it an amazing story? Would you walk into a room and say, “I’ve got to tell you this!” It has to have something of that for me.’

Lisa Gorton is a poet, novelist and critic. Her debut poetry collection,