Fiona Hardy interviews Alecia Simmonds

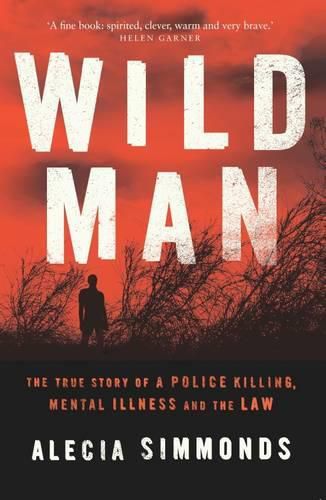

Our crime fiction specialist, Fiona Hardy, chats to author Alecia Simmonds about Wild Man.

On a strange dark night in April 2012, a peaceful gathering at a remote property in New South Wales was marked by violence when Evan Johnson threatened people with a crossbow and was shot by police. These are the bare bones of Johnson’s story; in Wild Man, Alecia Simmonds does some digging. We follow Simmonds as she heads deep into the heart of this case and similar ones. Her research reveals something telling in these times of unmitigated police violence, both here and overseas, about the lack of proper care available for those suffering from mental illnesses. Wild Man is a smart and compelling piece of journalism, that holds your hand even as it leads you into the darkness.

I was lucky to be able to be able to ask Simmonds some questions about the book…

The scene where you witness Electro-Convulsive Therapy is very raw and confronting. Do you think much of the problem with mental illness is that the solutions, as well as the problems, are hidden from the public eye?

I was really lucky to have a psychiatrist friend who allowed me access to the psychiatric ward for a day. If it was raw and confronting to read about, then imagine my shock upon seeing it! I still remember leaving the hospital feeling winded, shaken and ultimately confused.

As you say, part of the problem here is that the kinds of care I witnessed are hidden from the public eye, and so instead we draw upon a rich repertoire of filmic representations – from One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest to Janet Frame’s An Angel at my Table – as a substitute for reality. This blinkers us from very compelling arguments in favour of ECT, including the fact that it has very high rates of success for people suffering depression, for whom all other forms of treatment have failed. It also prevents us from questioning why we are horrified at certain forms of mental health treatment, but give our bodies over so complacently to other forms of invasive surgery (notably cosmetic surgery) with more dubious, or simply non-existent, medical foundations.

For me the most troubling part of ECT remains the problem of consent, the lack of adequate oversight and our tendency to seek bio-medical rather than social solutions for these problems. The woman I saw being given ECT would eventually have been spat out of hospital, with no step-down accommodation to go to and no vocational support or training, and would probably have ended up back on the streets until she suffered another ice-induced psychotic episode. At the point in time when I witnessed her drug-bloated body twitching to the 60-volt electrical shocks of the ECT machine, she’d already spent years in this cycle.

Which goes to the flip-side of your question: these problems are in fact not hidden from the public eye – we just fail to recognise homelessness, or even police shootings, as mental health issues. We see and read about mental health problems every day, we just call them something else.

While you have a legal background, you are still an ‘outsider’. Like many readers, you’re somewhat unfamiliar with the emotionally heavy coronial inquiry process as opposed to the media-saturated courtrooms of “objection” and angry banging gavels. This brings an immersive clarity into the experience – how did your narrative voice unfold?

It’s true that I have spent a fair portion of my life teaching and researching in law, so I was genuinely stunned to sit in on an Inquest and to find almost all the rules of evidence that go with an adversarial system banished. Rather than the staccato disruptions of a trial, you have the court performing a kind of therapeutic function: the Coroner was an immensely sympathetic man, the witnesses gave long (and, being hippies, at times incoherent and magical) narratives and the father of the man killed by police gave an unfathomably sad eulogy at the end. Given that I was surrounded by narratives, I felt that my task was to recount them in the most humane and empathetic way possible, but also to question these stories, to read them critically, against the grain, and to show why people may tell themselves a particular version of events. My narrative voice unfolded partly from the material I was given and partly from my own preference for writers who put all their doubts on the page – people like Helen Garner, who go to dark places and who question their own motivations. Narrative non-fiction is ultimately a conceptually promiscuous genre to write within: everything can be potentially relevant to the story – conversations with friends, dreams, newspaper reports, academic studies and empirical observations. It’s about crediting the reader with the intelligence to form their own conclusions from the panoply of arguments, images and narratives that you give them.

When Evan’s father talks about his love for his son at the inquest, I cried for everyone who had lost him. Was it difficult for you, who spoke to all these people who loved him, to disentangle your emotions from the story?

That’s lovely that you had that reaction, and in fact everyone I have spoken to who has read the book also cried in that part. As I said in the book, it was a moment in the Inquest when I was absolutely sobbing. We all were. And yes, it was immensely difficult to disentangle my emotions from the story, which is part of the reason why I didn’t. I instead used my feelings as a source of knowledge. I tried to show how our gut instinct or tears may lead us to conclusions that go against our ideological or academic positions. It doesn’t mean that they’re more authentic or truthful – simply that emotions can be tested against, and used alongside, other forms of reasoning.

As a story with multiple elements – psychosis, drug abuse, police killings, hypermasculinity – the book tackles all these issues while honing in one aspect: how the mental health system failed Evan Johnson and everyone around him. When someone dies threatening to kill people with a crossbow, we all say, “He should have been locked up” – when, as you point out, that’s only with the benefit of hindsight. As a rule, society detests seeing people stripped of their freedom. When it comes to the brain, the science is still imperfect. Can you see anything changing in the way people like Evan are handled?

I think that mental health is an immensely difficult area of public governance: how do you formulate policy for such a broad spectrum of illnesses or behaviours? Custodial care may be necessary in extreme cases like Evan’s, but obviously locking people up would be a terrible solution for most people suffering mental illness. As far as anything changing in the way that people like Evan are handled, I think that we’d need a government committed to increasing funding where it’s needed: preventative care facilities in the community, more psychiatric beds in hospitals, step-down accommodation, integrated drug and alcohol rehabilitation services and vocational support. We went from having 30,000 psychiatric beds in the 1960s to just under 2,000 public psychiatric beds today. These figures are extraordinary, really! And what they mean in practice is that the families or partners of people with mental illnesses are left performing an impossible labour of care: unpaid, untrained and vulnerable to violence.

Your description of the eerily beautiful landscape at the farm where Evan died – far from communication, down a remote and unpaved road, un-signposted – is vivid and unnerving. Are there other places that have given you such a visceral reaction, or seemed so haunted?

I lived in Paris for quite a few years and one of the things that I missed most about Australia was the bush: ‘her beauty and her terror’. And yes, I have had similar feelings when driving by myself through the red dirt country in Western Australia with no phone reception and just the howling emptiness of the land stretching before me. Of course, as I say in the book, these visions are a product of our colonial past. The land is obviously not empty, nor was it ever so – that feeling is indebted to a mythic erasure of Aboriginal people from the country. And this erasure in turn makes it haunted; haunted perhaps by history, by the violence and massacres that we fail to talk about. These unspoken stories of violence returns to us with a quickening of our pulse when we step into wild country; they return to us, as Ross Gibson has said, through that strange feeling of agoraphobia (a fear of its terrifying vastness) and claustrophobia (the eerie feeling that it’s in fact teeming with unseen bodies).

After the inquest, you speak to the coroner, a surprisingly appealing man who seems more emotionally invested in the case than expected. He warns about the dangers of how these stories are presented, saying: ”(Johnson) was not a character out of Deliverance or Wake in Fright or something like that, not some sort of monster who just shares a human form with the rest of us. He was a man who had lost his mind, and it is a genuine tragedy.“ Do you think the media reporting of these incidents, without adequate follow-up into their root causes and the fallout, feeds into everyone’s fevered view of these situations as spectacle instead of reality, therefore not having to consider further solutions?

Yes! That is such a big part of the problem. Evan Johnson’s case was reported by the tabloid press in the genre of ‘psycho attacks hippies with a cross-bow’ which contributes to stereotypes of people with schizophrenia as violent (they are in fact far more likely to harm themselves than anyone else) and sacrifices the humanity of the deceased for a sleazy marketable story. But similarly, in only focusing on the police shooting itself, we lose sight of much more interesting and compelling questions: why are police on the frontline of mental health? Are jails our new asylums? Why would we expect police to be able to play psychiatrist? I think that to properly answer these questions we need to look at the criminal law and our mental health system in tandem. We need to interrogate reality, not indulge in a pre-scripted horror show.

Are there any books about the history, present or future of Australia’s mental health care system you would recommend to readers?

One of the things that fascinated me as an academic was that Australia lacks any comprehensive history of our mental health system post-1950. So hopefully someone will write this soon and we can all get a better sense of what happened when we closed the asylums and adopted a policy of community care.

Until then, Stephen Garton’s Medicine and Madness is great, and in fact the best book I read on the issue was Barbara Taylor’s The Last Asylum. The Government Report, Not In Service, is an excellent compilation of oral testimonies from people who suffer mental illness, and for people into theory or philosophy, I don’t think you can go past Peter Sedgwick’s Psychopolitics or, for a counter-opinion, Michel Foucault’s Madness and Civilisation.