Ellena Savage on reading other people’s diaries

The main problem with feelings is that nobody wants to hear about yours. Except for me. And maybe the other literary voyeurs, whose preference is to read about your raw and pained inner life, but only if this pain of yours is elegantly expressed. For me, the best of these stylised confessions are contained in the notebooks of three great modern writers: the diaries of Sylvia Plath (1932–1963) and Susan Sontag (1933–2004), and the essays of Joan Didion (b.1934).

Plath, patron saint of the pained confessional, kept a journal from the age of eleven until her death. They are powerful reading, with episodic narratives and astutely observed characters (‘Linda is the sort of girl you don’t remember when you meet her for the second time’). But they also document Plath’s unstable mental health: ‘I don’t care about anyone, and the feeling is quite obviously mutual’; ‘I love people. Everybody’; ‘I do not love; I do not love anybody except myself’. Her husband, Ted Hughes, burnt her final journal because he ‘didn’t want her children to have to read it’.

Like Plath, Sontag kept a journal throughout her teenage years and beyond, arbitrating her intellectual growth rigorously. She is hard on herself, setting boundaries about her eating and reading habits, and about feeling lovelorn, often: ‘It hurts to love. It’s like giving yourself to be flayed and knowing that at any moment the other person may just walk off with your skin.’ Sontag’s journals are also full of delightful lists, of things she likes (‘fires, Venice, tequila, sunsets, babies, silent films, heights, coarse salt’), and things she dislikes (‘sleeping in an apartment alone, cold weather, couples, football games, swimming, anchovies’), and of the qualities she aspires to. And while Didion’s not primarily a diarist, her essays frequently meditate on the fashioning of oneself through the act of writing.

In the safety of my own (unpublished) journal, I reflect on profound topics, such as: The nature of love! The fear of rejection! Unfounded and unreasonable complaints against me! Weight gain! Being a grown-up person! and, Wondering who might have a crush on me! Compared with Sontag, and the immortal diary entry: ‘[t]alking like touching/Writing like punching somebody,’ there is very little in defence of my own efforts; very little punch in my prose.

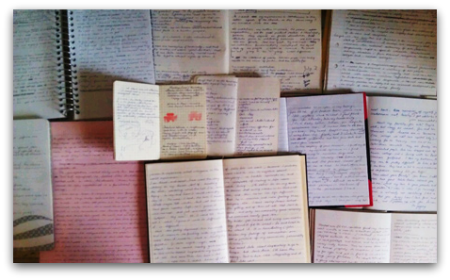

I began writing a journal consistently a few years ago after Mum forced Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way on me. Despite its off-putting self-helpish tone, this book offered a morsel of the best advice I’d ever received: write three pages of whatever in a notebook every day. What it doesn’t say is: when you write three pages of whatever in a notebook every day, your journals will not read like Plath’s. Strange and boring entries are hazards of this habit. In one bizarrely self-aggrandising entry, I write that ‘my supervisor believes I am a career liability’, and in another, that ‘I have measured out my life in emotionally unresponsive boyfriends.’ There are notes on some of my daily happenings, and profiles of people from my life, but only really if they bring about some kind of self-revelation. This is to say, these journals are all about me, me, me.

In her essay, ‘On Keeping a Notebook’, Didion writes that she imagines ‘the notebook is about other people. But of course it is not.’ She goes on to write that her ‘stake is always, of course, in the unmentioned girl in the plaid silk dress. Remember what it was to be me: that is always the point.’ And it is the point, even if Didion neglects to name it: those of us who are obsessed with our own secret business are desperate to see inside other people’s private lives as well. This desire is not predicated on a need to uncover the true nature of the other, but to imagine what it might be like to inhabit the other’s self-narrative.

There is so much artifice involved in writing one’s own narrative, in even describing one’s cognitive state at any given moment. Diaries are the ultimate bastard child of truth and fiction, bridging that unspeakable postmodern dilemma: whose truth? Just because you feel something doesn’t make it empirically true. And just because something’s not empirically true doesn’t make it false. Sontag writes, ‘In the journal I do not just express myself more openly than I could to any person; I create myself.’ That each of these writers diarises in crisp, considered prose is also important. They are using their notebooks to sharpen their tools, to train for work. Plath writes: ‘I will be stronger: I will write until I begin to speak my deep self … Every day, writing. No matter how bad. Something will come.’ Considering the curatorial role of the diarist – Which truth to reflect on? What to omit? – to what extent are these diarists considering posterity?

A few years ago, flirting with the idea of a relationship, a now ex-boyfriend and I exchanged a series of erotically charged emails. He and I were trying to impress each other, of course, but the thought also crossed my mind that, you know, we could make history. What if we became like de Beauvoir and Sartre? The question seemed pertinent at the time, and if this had actually happened, it would have been historically negligent to leave behind a trail of boring emails. So, I worked hard on them, just in case.

Plath, whose journal entries capture her lived moments as though they were discrete short stories, describes this phenomenon best – this consideration of posterity – in writing that her life ‘will not be lived until there are books and stories which relive it perpetually in time’. Her journals are, for the most part, composed in polished, confident prose. Could it be that everything a writer like Plath puts to paper is brilliant? Or are we reading the careful self-curation of the self-conscious diarist?

As Didion famously wrote in The White Album: ‘we tell ourselves stories in order to live.’ Few other artforms so deftly expose the curation of private selves as journals do. Reading them, then, is thrilling not only because they allow us access to great artists’ interiority and self-fashioning, but because they show us something about our own. As Sontag writes: ‘I live my life as a spectacle for myself, for my own edification. I live my life but I don’t live in it.’

Ellena Savage is the arts editor for