Maile Meloy

Maile Meloy earned both critical and popular acclaim with her compellingfirst novel

Liars and Saints,

a literary soap opera following 60 years inthe life of one Catholic family from World War II onwards. But it’s thequietly addictive, impressively diverse short-story collection

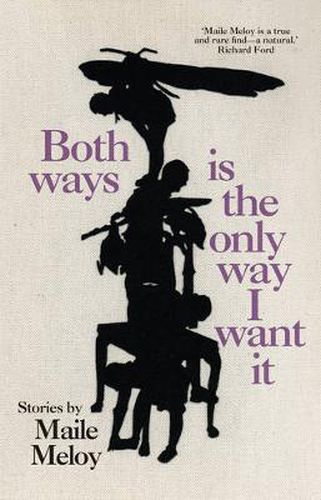

Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It

-

which comes with raves from Richard Ford and Ann Patchett as well as

The New Yorker -

that has made her a major American name. As she tells Readings’ Jo Case, itwas an accidental book, which all started with a last-minute raid on herproverbial ‘bottom drawer’.

Your first published book was short stories, your second was a novel about a family, and your third was a novel about the same family, under different circumstances. Now you’ve returned to short stories: this time an incredibly diverse collection. Do you have a favourite form – novels or short stories? What drew you to return to the short form?

I like going back and forth between the two. A few of the stories in Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It were written and published between the novels, but I didn’t have enough for a collection, and I was working on another novel. Then Granta magazine called, and they had put me on their list of ‘Best Young American Novelists,’ and they needed a short story for the issue, in a month’s time. I didn’t have any unpublished stories, but I remembered their list from 10 years earlier and I was thrilled to be on it. So I took out the handful of stories that I’d abandoned for some reason, but that were close: something in them hadn’t worked, or I could never get the end right, or magazines had rejected them and I’d gotten discouraged. Time is the best editor, and enough time had passed that I could see ways to fix them. I sent one to Granta and kept working on the others, and then I got used to that shorter pace again, and wrote a couple of new stories. And then I realized I had a collection. So in a way, it’s all because of Granta. And I’m glad I had a reason to return to those stories, because I think the fact that there was something difficult in them meant there was something promising in them.

Many of your characters are outsiders, or uncomfortable in their own skin: the lonely cowboy in ‘Travis, B’; Steven in ‘Lovely Rita’, who keeps losing the people (and even places) he is closest to; the damaged and damaging girlfriend of a convicted murderer in ‘The Girlfriend’; the privileged reclusive widower in ‘Agustin’, who dislikes his daughters and longs for a former lover. What draws you to these types of characters, as a writer?

I guess that people who are perfectly comfortable in their own skin and are insiders aren’t as interesting to me. I’m not sure I actually know any people like that. I think to be human is to have a desire for connection that can’t always be fulfilled.

One of the things I love about your writing is that you don’t shy away from the flaws in your characters – even the most sympathetic are never two-dimensional. The protector of his dead best friend’s girl also desires her for himself. A grieving father confronts the girlfriend of his daughter’s murderer, and tries to exploit her vulnerability to get to the truth, even while she tries to turn him to her advantage. Is this balance of light and shade in your characters – the constant shifting of sympathies – something you consciously work to achieve?

Yes. Again, I don’t know anyone without flaws, and I want the characters in the stories to be people, to live and breathe. When I was almost finished with Liars and Saints, which follows a single family from World War II to the millennium, I watched the BBC nature series Blue Planet. And I was struck not only by the amazing photography but also by the storytelling in it. You’re with a baby seal, hiding beneath the ice, and you see a giant polar bear’s paw pounding down through the snow, and reaching in. The baby seal cringes and tries to pull away, and you want that baby seal to live. But then the focus shifts, and you’re up on the vast, empty, white ice with a mother polar bear and a tiny, prancing cub. There’s nothing else in sight, and she’s thin and starving and can’t make any milk for the cub unless she gets something to eat. So she has to find a baby seal, buried somewhere under all that ice. And you want her to find a baby seal! I realized that I was trying to do something like that with the alternating perspectives in the novel. My characters weren’t trying to eat each other, but they were coming into conflict, and challenging each other’s deeply held beliefs, in the way that the latter part of the 20th century challenged people’s beliefs and their concept of the world. But I didn’t want it to be about the 20th century, I wanted it to be about people. And I wanted the reader to be on the side of the character whose chapter it was, and to understand where they were coming from, and then to be right there on the side of the character in the next chapter who wanted something completely different.

There is a lightness of touch in your stories – a simplicity that, on close inspection, seems likely to be seamless crafting. How long do you work on an individual story? Do you labour to get individual details just right, or does it flow naturally? (Or is the truth somewhere in the middle?)

It depends on the story. Sometimes, if I know where the story is going, it rushes along and I feel like I’m just following it, typing. Mostly it’s harder, and stops and starts. But in either case, I go over the story endlessly. I add and change details, and try to make everything vivid, so that other people will be able to see it as clearly as I do. But I’m also listening for the rhythm of the sentences and the rhythm of the story. I’ve realized lately how much that matters to me. I go over the story until nothing in it stops me anymore, and then I go over it again.

I think my favourite story is ‘Two-Step’, about an awkward encounter between a wronged wife and the woman who is in the process of stealing her husband – it’s a story that keeps you guessing about the intentions of its characters, and who knows what about each other. It’s a wonderful illustration of how people can talk around a topic without ever directly addressing it. Is that a theme you enjoy exploring – the unsaid?

Yes—what people are saying beneath what they’re saying is always interesting to me. I also wanted to write a story in which what you know and think about the characters changes, and the power shifts, so that it starts out seeming like one kind of situation and then turns, and turns again.

Place seems very important to your stories, particularly those set in America’s mid-West, with the dangers of black ice on the roads, the fishing, the deep snows. The landscape seems both beautiful and isolating. How does the setting inform your stories? Do you come up with the setting first and characters afterwards, or do they evolve side by side?

I usually have a place in mind first. In most cases it’s essential to the story, and the story couldn’t happen without it. In the story ‘Travis, B.,’ a young woman takes a second job on the other side of Montana, and has to drive nine hours to get there, twice a week. In her exhaustion and disorientation, she meets a young cowboy who recognizes that she comes from another world, even though they’re both from Montana. The story couldn’t exist without the vast breadth of Montana to drive across, because the distance gives their actions drama—and it was the idea of that drive that I started with.

The last story in the collection, ‘O Tannenbaum,’ could only take place in rural winter, in the woods, where people cut down Christmas trees a long way from anywhere, and pick up hitchhikers because you can’t leave people out in the snow.

In terms of process, I tend to write dialogue and character first, and then go back to add the details of the setting (wherever that might be) and try to make the world around the characters visible. I think that’s because I’ve already decided what the setting is, and have a handle on it, but I don’t know who the characters are or what they’re going to do.

Who are your writing influences? Are there any authors whose writing inspires you, or informs your work?

I try to read a lot of different writers so I won’t be overly influenced by any one of them. And it’s been different for every book.

For Half in Love, it was J.D. Salinger’s Nine Stories, Philip Roth’s Goodbye, Columbus, and the collected William Trevor and John Cheever stories.

For Liars and Saints, it was Merce Rodoreda’s The Time of the Doves, which is about an innocent female character in wartime; Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall, which has a beautiful three-part structure; and Cheever’s The Wapshot Chronicle, which is about a family, and is told from alternating perspectives, and made me think that what I was writing might be a novel.

For A Family Daughter, it was Italo Calvino’s If On A Winter’s Night A Traveller, Philip Roth’s The Counterlife, and Tristram Shandy, even though I haven’t read the whole novel.

For Both Ways Is the Only Way I Want It, I read J.D. Salinger’s Nine Stories again, and Sherwood Anderson’s Death in the Woods and Other Stories, and Ivan Bunin. I tried hard to be influenced by Bunin. I read his wonderful story ‘The Gentleman from San Francisco’ three times in a row and became desperate to write an omniscient Russian short story. It didn’t work out, but I haven’t given up yet.