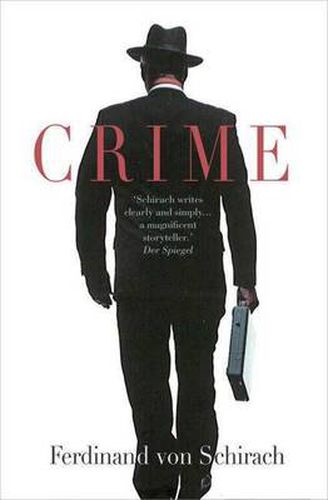

Ferdinand von Schirach

Johanna Adorján, author of

The Berlin criminal defense attorney Ferdinand von Schirach has joined the ranks of writers with his first book of short stories. A conversation about the depths of the human soul and the empirical advantages of writing attorneys.

The stories that the Berlin criminal defense attorney Ferdinand von Schirach offers us in his first book are true. All of them are based on cases he has experienced in his law practice. Along with jealousy, greed, lust, despair, and passion, the question is as always Whodunit – allowing for the fact that the more critical question is always Why. A wonderful debut, one that grips you from the very first page and never strikes a false note.

After forty years of marriage an elderly doctor takes an axe to his wife; a leading industrialist is indicted for the murder of a prostitute; a woman kills her brother…all these stories in your book are ones you have had firsthand knowledge of in your career as a lawyer. They read as if your working life is quite high-colored.

Well, it’s not un-exciting. There are those who say the reason they become defense lawyers is simply that people have such extraordinary stories to tell. These people come to your offices and tell you things that have actually happened. Where else could you get this? It’s like really good movies, and actually more interesting. But of course there are also the wearying bits, sometimes you get a little tired of the weeping wives of defendants who are being held in custody. Or in cases of white-collar crime, where there are no so-called victims, it can also try your patience that everyone who makes an appointment is absolutely innocent.

Given your experience, you could probably write extremely successful crime shows for television.

Most people who write crime stories have no experience of real-life crime; they sit in cafes drinking cappuccino and create a world of their imagination. It’s why they spend so much time spelling out how someone used a knife and fork, that the tablecloth was frayed, or that the sky turned overcast…in that respect I’m lucky. I just have these stories, and I can tell them in a relatively unembroidered way.

The longer form doesn’t suit you?

The average jury trial lasts five to ten days. Within this time frame, you can get to know someone very well, and the judges, who by and large have a high ethical standard, trust themselves to be able at the end of this time to render judgment on someone. The short story is the literary form that corresponds to this. There is no need to write expansively in order to capture character. It is of course much more beautiful to be able to write like Marcel Proust and take 60 pages to describe the scene when the countess enters the room, but that is not what I do, and each of us can only write according to our individual natures.

As a lawyer, you are bound by the rules of confidentiality. You must have had to change both names and details so that none of this could be googled.

Yes. Did you try it?

I tried to find the case of the two hooligans who were killed with absolute precision on a Berlin suburban railway platform by an anonymous-looking man after they’d threatened him with a baseball bat. I didn’t turn up anything.

The case was never mentioned in newspapers. Of course it is my duty to protect the personal rights of any client I represent, and I have done so in every case. Any breach of confidentiality would be a criminal act.

In this story it becomes clear that the anonymous-looking man was most likely a professional hit man who had carried out a killing in Berlin that same morning. You got him acquitted. How do you feel as a defense attorney when you’re defending someone like that?

It really is no different for a defense attorney than it is for most people – by and large, you assume the majority of your clients are guilty. But that is never the point. I do not think about whether someone is guilty or not; the only issue is whether the evidence is sufficient to convict someone. It’s quite different. The truth captured on film is something you only get in TV dramas – courts deal with another kind of truth, one that is brought to light by the criminal justice system. Imagine that you’re a judge. Five witnesses appear before you and say the car was white. Actually, the car was green. As a judge, you have no alternative but to rule that the car was white. Every witness you have heard testifies to the same thing. This particular concept of the truth, if you wish to look at things from the point of view of judicial philosophy, also gives rise to the particular responsibility of the defense attorney. He must prevent the court from settling too quickly on a particular truth. In this position, if I were to occupy myself with questions of moral guilt, I would have failed in my professional duties…I should have taken Holy Orders instead.

Is it possible to be an effective defender of people you fundamentally don’t like?

I for one can’t do it. There are always unsympathetic defendants, but I will not defend anyone I find repellent. There are also whole categories of offenses I don’t choose to involve myself in. Child abuse for example. These people also have the right to a defense lawyer, but it doesn’t have to be me.

As an author, you bring an unprejudiced eye to all your perpetrators.

I’m not a 1968-er, I don’t believe we’re all obliged to have understanding for everything. We’re living in an extraordinary time, there’s no war, despite the world economic crisis we’re doing very well, and then again there are a handful of people who turn out to be exceptions and do idiotic things. We can afford ourselves the luxury of paying proper attention to them.

You are the grandson of Baldur von Schirach, the former Gauleiter of Vienna who was found guilty at Nuremberg. Did this family history sensitize you to issues of crime, guilt, and punishment?

Oddly enough, it was only a few weeks ago that I asked myself for the first time if my grandfather’s guilt had any bearing on my choice of profession. If his guilt was one cause of why I occupy myself with guilt on a daily basis, then it was certainly an unconscious decision. But I am pretty sure I can exclude it. Of course I was interested in him while I was a student, because the Nuremberg Trials are an interesting subject, and because I really had no choice, given my family name.

Mark Twain said, “Truth is stranger than fiction.” Do you agree?

Absolutely. Life is full of unexpected changes of direction or things that follow no kind of logic. For example I once defended a major drug dealer who was mugged and robbed of the money he intended to use to pay for a consignment. And this man immediately suspected his own supplier. The supplier’s boss, however, believed him to be innocent. But when the supplier demanded money from his boss because of the failed delivery, the boss suddenly decided he was guilty. Logically speaking, it’s ridiculous. Any of us would think it was a particular sign of honesty to calculate reimbursement for the failed deal, because an expenditure had been incurred. But this particular boss thought, OK, now I’ve got the bastard. Stories like that, beyond normal logic, happen all the time.

What kind of people show up in your office? What do major drug dealers look like?

It’s normal not to recognise criminals most of the time. That only happens in movies. And usually only because the music gives you the dramatic cues. But when you’ve been doing it as long as I have, you can often recognise them quite early on. Most policemen do it too.

You sometimes see people in the street and you think, “he’s got something to hide.”

No, I think: he’s a defendant! In the film, M – A City Seeks a Murderer, the commissioner says, “I recognise my pigs by the way they walk.” I wouldn’t put it that way, but funnily enough, there’s a fair amount of truth in it. For example, you can always recognise conmen. They always talk too much, they’re insanely polite – after so many years defending people, you simply know sometimes that something doesn’t add up.

How dangerous is Berlin? The cases you take on in your elegant offices sound a little as if they emanate from the Bronx.

Berlin is certainly very large, and there are – as most people don’t know, perhaps just as well – genuine parallel worlds. But the long term hardened criminals tend to remain in their own particular world and it’s one you’ll never come in contact with. The totally normal people who commit crimes are different. The same things happen to them that could also happen to us. At some point they do something that they didn’t want to do. For example: Imagine you’ve just been left by your boyfriend. And you know the single stupidest thing you could do is to call him up. You know this from experience, it’s also what your best girlfriend is telling you, you know it’s absolutely idiotic to pick up the receiver – and yet you do it. It’s not dissimilar when it comes to crimes. There are very few people who get out of bed in the morning and say, “Great day, today I’m going to commit a crime.” Mostly the way it happens is that situations develop, things escalate, and at some point something happens. Most people think there’s a qualitative difference – I think it’s a quantitative difference. When you yell at your boyfriend, it’s one little tiny step and it can escalate until you stab the scissors into his neck. Of course the inhibition threshold for yelling is lower, but the transitions are fluid, which is why any one of us is always in a little danger of committing a criminal act.

This interview