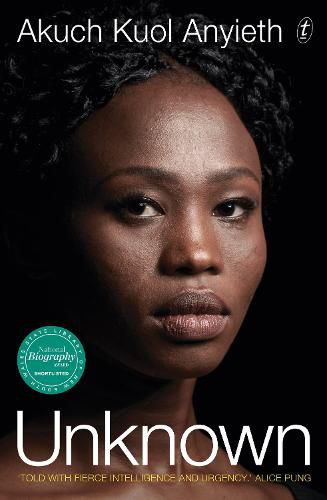

Unknown: A Refugee’s Story

Akuch Kuol Anyieth’s Unknown is a remarkable memoir. It’s a homage to the strength of her mother in protecting her family against all the odds, a story of sadness, anger, humour, determination, survival and love.

In January 2006, Mathew and Mama took Gai and me to enrol at Western English Language School on South Road in Braybrook.

When we arrived, we waited in front of a little glass booth while Mathew told the woman sitting inside that we had an appointment with the principal. She picked up a phone and spoke to someone, before pointing us to chairs lined up against the wall. Everywhere we went in this new country, people sat behind glass windows and pointed us to chairs. We were constantly shocked by this behaviour. In Kakuma and Nairobi, when a visitor arrived, you got up and greeted them, asked how they were, how their family were doing, asked about the kids, if they had any, and then warmly offered them a seat. The way white people acknowledged others here felt unwelcoming and disrespectful, but it seemed to be completely normal.

After a while, a tall woman emerged from an office on the far left of the hallway. We all stood up to greet her, our eyes downcast, to show respect. In Kenya it was also respectful to call a woman in her position ‘Madam’. She shook our hands in turn and led us back to her office. She handed Gai and me enrolment forms – which turned out also to be tests to assess how much English we knew – and through Mathew asked us to sit in opposite corners of her office while we filled them in.

The first question was ‘Name’ so I wrote my name, the second was ‘D.O.B.’ . I had no idea what that meant, so I left it empty. On the next line, I didn’t know how to spell our address, so left that empty as well. The questions became more complex. As I was attempting to read the last question, which seemed to require us to write a brief description of our family, the principal asked for the papers back. I had only written my name; it was the only question I could answer.

I hung my head in shame as I handed it to her, and I could see Gai doing the same. The principal then explained that the results of our tests would determine what grade we would be allocated to, and how long we stayed in Language School before we were considered ready for high school. Again, just like the woman at Centrelink, her English was completely foreign to us. We did not understand a single word until Mathew interpreted for us.

Our first day at Western English Language School was overwhelming: there was so much to remember, on top of the fear of the unknown, and the fear of failure. When we arrived at the front office, the principal took us to our classes. I was in the beginner level for those of high school age and Gai was in the equivalent level for primary school students. The principal introduced me to my teacher, then took Gai to his class.

My teacher was a young woman, probably around, Atong’s age, or a bit older. She was very welcoming, and introduced me to the rest of the class, before pointing me to an empty seat in the front row. I guess no one else wanted to be that close to the teacher.

There were only ten students in the class, all from different cultural backgrounds, South Sudanese, Ethiopian, Asians, Middle Eastern. Next to me was an Ethiopian girl with beautiful thick, wavy hair that bounced on her shoulders as she turned her head. She was the quietest in the class. The rest of the students all called out at the same time when the teacher asked a question.

‘Please raise your hands if you know the answers, don’t shout your answers,’ the teacher insisted, but no one obeyed her.

A bell rang. I watched the other students, then took my sandwich and apple juice from my bag while everyone hurtled out as if a ticking bomb was in the room.

When lunchtime came, none of us had any lunch to eat because we had eaten our sandwiches instead of our fruit during the recess break. We didn’t know that the trick was to eat a good breakfast so you were not starving by recess – to eat fruit for recess and keep lunch for lunchtime.

Our problem was that we couldn’t eat before school. In Kakuma, in order to eat in the morning, your mum had to wake up early to make you porridge, which most families couldn’t afford. If we didn’t go to school early to line up for the school porridge, we ended up not eating in the morning, and often not at lunchtime either.

It turned out that Western English Language School served toast, milk and fruit before classes, for the kids who couldn’t have breakfast at home for whatever reason. We tried to make it in time, but usually missed it as we had dramas at home almost every morning.

There were only a few South Sudanese families living in St Albans, not more than five that we knew of. All the mums – and the dads who weren’t back in South Sudan – went to AMES in St Albans and their children attended Western English Language School and the nearby high schools. Everyone knew each other, and of course we followed our traditional social practice of visiting each other’s houses without prior arrangement. Everyone was always welcome. Some of the families also attended the Sunday afternoon service with us at the Anglican church on Alexina Street.

But there were no other South Sudanese on Theodore Street, and we felt alone. All our neighbours minded their own business. Their doors were always shut. When we walked by their houses, we only ever saw them getting in or out of their cars. And when we happened to pass them on the footpath while they were walking their dogs, instead of saying hello, they just gave us an aloof nod.

It was bewildering. How could people live in such isolation? Maybe that’s just how white people live, I thought to myself. Maybe you’re not meant to greet people, not meant to knock on someone’s door and say, ‘Can I have a piece of onion because I ran out and I can’t go to the shops – I need to prepare a meal for my family.’ Maybe we were just meant to stay home and not bother other people.

Where we came from, our neighbours were like family, and we knew almost everything about them. I wondered if our new neighbours here were afraid of us – perhaps, because we couldn’t speak English, they felt they couldn’t knock on our door and welcome us.

And we must have looked alien to them as well; we were the only dark-skinned people on Theodore Street. And, whether we liked it or not, some people form prejudices based on physical appearance. We looked different and we lived differently. Our neighbours were quiet, indoor types. We were loud and spent every sunny day in our front yard. We craved the heat. If I give them the benefit of the doubt, maybe our neighbours wanted to be friends with us but didn’t know how to approach people who didn’t look like them. Maybe they were waiting for us to make the first move. Who knows? In the end, we had to come to terms with the fact that, in this different country, people did things differently. We had to learn how to mind our own business.